Deep in the labyrinthine tags of TikTok, a group of teenage occultists promise they have the power to help you change your life. ‘Manifesting’ influencers – as they’ve come to be known – promise their legions of viewers that, with the right amount of focus, positive thinking and desire, the universe will bend to their will. ‘Most of these people [who manifest] end up doing what they say they’re going to do and being who they say they’re going to become,’ insists one speaker on the mindsetvibrations account (600,000 followers). Another influencer, Lila the Manifestess (70,000 followers) offers a special manifestation (incantation?) for getting your partner to text you back. (‘Manifest a text every time.’) Manifest With Gabby tells her 130,000-odd followers in pursuit of ‘abundance’ about ‘5 things I stopped doing when learning how to manifest’ – among them, saying ‘I can’t afford.’

It’s not just TikTok. Throughout the wider wellness and spirituality subcultures of social media, ‘manifesting’ – the art, science and magic of attracting positive energy into your life through internal focus and meditation, and harnessing that energy to achieve material results – is part and parcel of a well-regulated spiritual and personal life. It’s as ubiquitous as yoga or meditation might have been a decade ago. TikTok influencers and wellness gurus regularly encourage their followers to focus, Law of Attraction-style, on their desired life goals, in order to bring them about in reality. (‘These Celebrities Predicted Their Futures Through Manifesting’, crows one 2022 Glamour magazine article.)

It’s possible, of course, to read ‘manifesting’ as yet another vaguely spiritual wellness trend, up there with sage cleansing or lighting votive candles with Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s face on them. But to do so would be to ignore the increasingly visible intersection of occult and magical practices and internet subcultures. As our technology has grown ever more powerful, our control over nature seemingly ever more absolute, the discursive subculture of the internet has gotten, well, ever more weird.

Sometimes it seems like the whole internet is full of would-be magicians. ‘WitchTok’ and other Left-occult phenomena – largely framed around reclaiming ancient matriarchal or Indigenous practices in resistance to patriarchy – have popularised the esoteric among young, largely progressive members of Gen Z. The ‘meme magicians’ and ‘Kek-worshippers’ – troll-occultists of the 2016-era alt-Right – have given way to a generation of neotraditionalists: drawn to reactionary-coded esoteric figures like the Italian fascist-mage Julius Evola. Even the firmly sceptical, such as the Rationalists – Silicon Valley-based members of tech-adjacent subcultures like the Effective Altruism community – have gone, well, a little woo. In an article for The New Atlantis, I chronicled the ‘postrationalist’ turn of those eager to blend their Bayesian theories with psychedelics and ‘shadow work’ (a spiritualised examination of the darkest corners of our unconscious minds). As organised religion continues to decline in Western nations, interest in the spooky and the spiritual has only increased. Today, witches might be one of the fastest-growing religious groups in the United States.

Magic, of course, means a host of things to a plethora of people. The early 20th-century anthropologist Edward Evans-Pritchard used ‘magic’ to describe the animistic religious sentiments of the Azande people, whom he deemed primitive. There is folk magic, popular in a variety of cultures past and present: local remedies for ailments, horseshoes on doors, love charms. There is fantasy magic, the spellcasting and levitation and transmogrification we find in children’s novels like Harry Potter. And there is magic-as-illusion, the work of the showman who pulls rabbits out of hats. But magic, as I mean it here, and as it has been understood within the history of the Western esoteric tradition, means something related to, yet distinct from, all of these. It refers to a series of attempts to understand, and harness, the workings of the otherwise unknowable universe for our personal desired ends, outside of the safely hierarchical confines of traditional organised religion. This magic comes in different forms: historically, natural magic, linked with the manipulation of objects and bodies in nature, was often considered more theologically acceptable than necromancy, or the calling on demons. But, at its core, magic describes the process of manipulating the universe through uncommon knowledge, accessible to the learned or lucky few.

The canny reader may note that magic as I’ve defined it sounds an awful lot like technology, given a somewhat spiritualised sheen. This is no coincidence. The story of modernity and, in particular, the story of the quixotic founders of our early internet (equal parts hacker swagger and utopian hippy counterculture) is inextricable from the story of the development and proliferation of the Western esoteric tradition and its transformation from, essentially, a niche cult of court scientists and civil servants into one of the most influential yet least recognised forces acting upon contemporary life.

From the Renaissance humanists onwards, nearly every major proponent of what we might loosely call modern, liberal, democratic, technologically saturated life was involved with, or at least influenced by, intellectual and philosophical movements – from Hermeticism to Freemasonry – that were laden with occult promise. That promise? That human beings could – indeed should – seek, contra Biblical fiat, to maximise their knowledge and technical capacity in order to transform themselves into gods. This differs from the Dan Brown vision of history, where a shadowy cabal of Freemasons (or Illuminati) secretly moves the gears of history. Rather, I’m suggesting that the once-transgressive ideology underpinning the Western esoteric tradition – that our purpose as humans is to become as close to divine as possible – has become an implicit assumption of modern life. At the extreme reaches of Silicon Valley culture, it’s an explicit assumption.

Earlier this year, the tech titan and Braintree founder Bryan Johnson, who made headlines for his multimillion-dollar quest for life extension, boasted on Twitter of his status as a new Messiah. ‘I am not a tech tycoon or biohacker,’ he wrote, ‘I am playing for societal scale philosophical transformation, competing for the status and authority of Jesus, Satan, Budda [sic], and similar.’ More and more of us – regardless of religious affiliation – see our relationship to nature and culture alike as one of entitled control: Of course we should harness the powers of the universe to serve our own ends and live our best lives. Of course we are, or soon will be, functionally divine. But when did all this start?

In the Renaissance, a controversial humanist scholar named Giovanni Pico della Mirandola penned his Oration on the Dignity of Man. Influenced by orthodox Christianity, the Jewish Kabbalah, Arab philosophy, and the revival and reimagining of classical Greek thought known as Neoplatonism, Mirandola believed that the defining characteristic of human beings was precisely that they are born to take the place of God. In his Oration, Pico retells the familiar story of Creation told in Genesis 1: God creating the world and ultimately humanity. But Pico’s God is a less omnipotent being than the Bible’s. He has only a limited number of mental ‘seeds’ – a Neoplatonic image signifying, essentially, divine implantation of purpose: or, the thing that makes, say, stems grow into flowers, or trees stretch for the heavens. By the time he gets to humanity, Pico’s fatigued God has exhausted his supply of such seeds. So he makes Man without one. Or: to put it more accurately, he makes Man to determine his own. ‘Adam,’ says God, ‘you have been given no fixed place, no form of your own, and no particular function, so that you may have and possess, according to your will and your inclination, whatever place, whatever form, and whatever functions you choose.’ Where other creatures have a ‘fixed nature’, God tells Adam ‘you, constrained by no laws, by your own free will … will determine your own nature.’

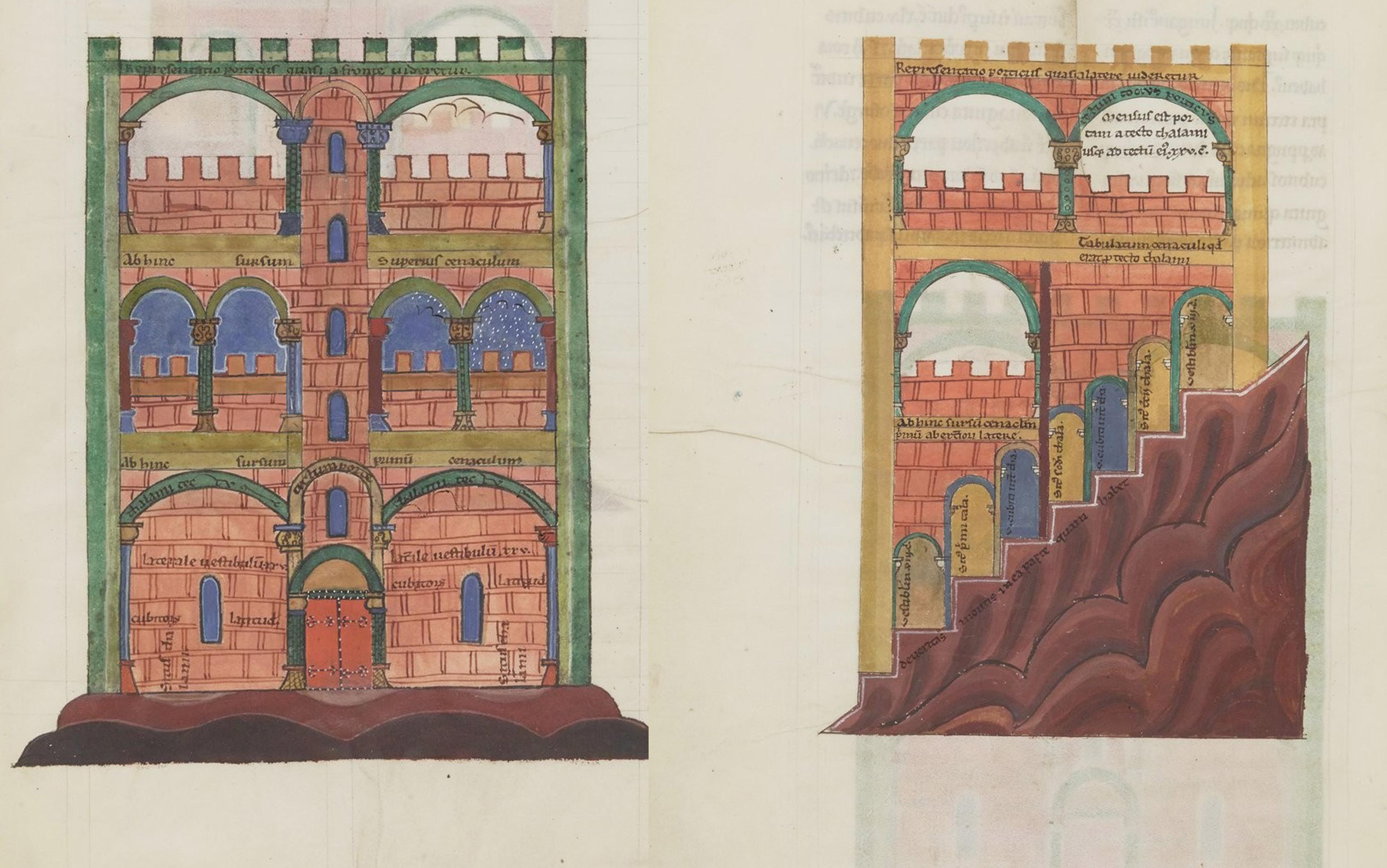

Pico’s writing can be read as a particularly extreme example of Renaissance humanism, as part of a general trend of early modern writing that emphasised human freedom and creative power, in contrast with medieval visions of human life as but a part of a wider, interconnected social and natural order – visions commonly associated with the theology of St Thomas Aquinas. But to understand Pico better, we must look at the texts that influenced him most: a mysterious compendium of writings known as the Corpus Hermeticum, or the Hermetica. Pseudonymously written in the first few centuries CE, likely in the philosophical melting pot of Hellenistic Alexandria, the 17-part Corpus Hermeticum purports to be the writings of a mysterious demigod, Hermes Trismegistus, associated with the Greek trickster-messenger god Hermes and the Egyptian god of writing, Thoth.

Human freedom, intellectual endeavour, progress – all were signs that humanity’s destiny was to become God

Blending philosophy, scripture, natural science, alchemy, astrology and magic, the Hermetica as a whole represents a distinctive vision of human transcendence. The mysterious Hermes Trismegistus is a self-made god: a mage with near-divine control over both the scientific and magical worlds – they are, in the Hermetica, the same world. As Hermes learns in Book XI of the Hermetica (from the translation by G R S Mead):

If, then, thou dost not make thyself like unto God, thou canst not know Him. For like is knowable unto like [alone]. Make, [then,] thyself to grow to the same stature as the Greatness which transcends all measure; leap forth from every body; transcend all time; become Eternity.

The highest purpose of the human is to transcend humanity through knowledge, and become creator. The material (mortal) decaying stuff of our physical animal bodies exists only to be overcome via a spirit linked with knowledge and will.

Central to Hermetic thought was the tenet: ‘As above, so below.’ Everything is connected, from the movement of the stars and the planets to the internal workings of an insect. Understanding these secret connections, and harnessing them, was the key to a successful magician’s art. Central, too, was the occult nature of the mage’s knowledge. The mage saw things, and connections, that ordinary or uninitiated people could not.

Supposedly lost for centuries, the Corpus Hermeticum was ‘rediscovered’ in the 15th century, when another Renaissance humanist (and occultist) Marsilio Ficino discovered a manuscript in the library of his patron, Cosimo de’ Medici, and translated it into Latin. Its humanistic vision – its transhumanistic vision! – was enormously influential not just on Pico and Ficino, but on the Renaissance intellectual project as a whole. Human freedom, human intellectual endeavour, human progress – all these were not merely allowed by God, such that human beings might better fulfil God’s purpose for them, but were signs that humanity’s destiny was to become God, bending technological power to accord with their own desires and wills. As the Hermetic-influenced Renaissance humanist Giordano Bruno put it, man’s purpose is ‘to fashion, other natures, other courses, other orders’ so that ‘he might in the end make himself god of the earth’. Scientific progress was thus bound up with spiritual development – a development predicated, in opposition to the authoritarian Catholic Church, on the notion of making manifest one’s own desired purpose. While, for much of Western religious history, the mythic figure of the would-be knower who rebels against God was a cautionary tale (Lucifer, Adam and Eve, the Tower of Babel, Prometheus), here, the seeker of knowledge was a model for human advancement.

Hermetic ideas diffused across a range of movements in the early modern period. The Rosicrucians, for example, dabbled in human self-transcendence and attracted scientific luminaries such as the German physician Michael Maier, the English mathematician Robert Fludd, and Isaac Newton, who spent decades of his research life trying to create the alchemical ‘philosopher’s stone’. Hermeticism’s tendrils could also be felt in the rise of ‘speculative’ Freemasonry, which swept the guild structure, rhetoric and imagery of medieval masons into the ‘free-thinking’ world of the 18th century to create a ritualistic structure at once distinctly anticlerical and thoroughly religious. Freemasons such as Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, as well as several signatories of the US Declaration of Independence, blended intricate ceremony with carefully crafted regalia as meticulous as any church’s vestments or liturgy into a kind of worship of human freedom.

It would be a mistake to think of Hermeticism as a codified religion: with a clear and consistent set of tenets and membership criteria. The Rosicrucians, Masons and, later, Hermetic-tinged groups like the Golden Dawn and Theosophists each had their own rites, rituals and subgroups. Nor was Hermeticism the only magical system in play; Solomonic magic derived from Arab and Kabbalistic sources also stressed self-divinisation (controlling angels and demons alike by calling them by their proper, yet secret, names). What these movements shared was a faith in human self-transcendence as the highest spiritual good. Those who participated most fully in the project of self-divinisation through knowledge could, in some sense, be said to be the most human: the elect whose ability to understand reality was bound up in their ability to shape it. Politically as well as theologically, their ‘priestcraft’ set them against the Christian ecclesiastical establishment.

In this, early modern occultists were not unlike today’s peddlers of meme magic: claiming a populist stance against the elite ‘cathedrals’ of academic and journalistic establishments, while affirming the distinctly esoteric ideal of the lone genius (or elite cabal) capable of seeing what the ‘sheeple’ cannot. Today’s meme magicians likewise claim access to the hidden forces underpinning the global order, which they seek to harness for their own ends.

Whoever shapes the perception of others, in order to get what they desire, is practising magic

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, transhumanist magic began to focus less on knowledge of the world, natural or otherwise, and more narrowly on the power and control of the mage himself. The controversial diabolist Aleister Crowley’s Thelema (a movement as much influenced by visions of a Nietzschean Übermensch as by Hermeticism’s demigods) and the New Thought tradition from the US, for example, focused on mastering one’s own internal psychic energies. (Indeed, Thelema takes its name from the Greek word for will.) What we want – and how we focus that energy of wanting – doubles as the primary engine of reality. Which, of course, only the most godlike among us can shape. Whether the creator-God is absent, abdicated or usurped, Man’s role remains the same: to take his place. Crowley’s most famous maxim takes Pico’s vision of a self-fashioning self to its natural conclusion: ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.’

In what is perhaps Crowley’s most powerful successor ideology, the ‘chaos magick’ that grew out of the 1970s London punk scene, we can find the most obvious genesis of modern internet culture. Heavily influenced by the writings of one-time Crowley acolyte Austin Osman Spare, chaos magick dispensed with Hermetic associations – and the lattice of meaningfulness that connected them – altogether. Rather, for the chaos magicians, meaning was not something to be discovered, but decided. Reality came to rest primarily with human perception, so that changing human perception was not to lie, but to reimagine reality itself. Or, as one chaos magician of the time put it: ‘chaos magick is the art of forming the unformed energies of creative chaos into a pattern leading to the outcome of the magician’s desire.’ The major tenet of traditionalism – that there was a secret initiatory truth underpinning all major world religions – collapsed into nihilism: there is no such thing as truth at all. All that matters is what we can make people believe.

As the occult historian Gary Lachman writes in Dark Star Rising (2018), his account of magical tendencies in modern internet culture: ‘for chaos magick the idea of “truth” or “facts” is anathema.’ Whoever shapes the perception of others, in order to get what they desire, is practising magic. Here, magic is effectively denatured, stripped of its supernatural and mystical elements and revealed instead as the mage-like ability to bend the social imaginary to his will. ‘As above, so below’, in this context, refers less to the relationship between, say, plants and planets, than to the relationship between the human psyche and human cultural life. Change one person’s mind – and you might change the world.

Enter our internet pioneers. Steeped in mid-20th-century counterculture, the futurists, technologists and inventors who would come to shape Silicon Valley culture shared with their Hermetic forebears an optimistic vision of human self-transcendence through technology. Freed of our biological and geographic constraints, and of repressive social expectations, we could make of cyberspace a new libertarian Jerusalem. As early as the 1960s, the futurist Stewart Brand, the publisher of the hippy counterculture bible the Whole Earth Catalog (1968), rhapsodised about how, in the modern world, the ‘realm of intimate, personal power is developing – the power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment,’ concluding that ‘We are as gods and might as well get good at it.’ Early cyber-enthusiasts and futurists – more than a few of whom, from Terence McKenna to Robert Anton Wilson, dabbled in occult, mystic or magical practices – saw in the prospect of cyberspace a new spiritual terrain for self-divinisation. Freed of bodily constraints and geographic limitations, the internet could help us at last achieve the magical dream of transcendence.

In an article for Wired magazine in 1995, Erik Davis chronicled one ritual, performed by Mark Pesce – the founder of the early programming language known as VRML (virtual reality modelling language) – during an event that was equal parts technopagan ritual and scientific summit. Heavily structured along traditional Hermetic and Rosicrucian lines, the ritual involved four personal computers, taking on the customary role of elemental watchtowers, running a graphical browser that depicted a ‘ritual circle’, pentagrams and all. An observer chanted: ‘May the astral plane be reborn in cyberspace.’ The internet seemed to be a place where humanity could achieve a more democratic and collective magical rebirth. After all, it was a place where, in the absence of our physical bodies and social restrictions – we could exist solely as manifestations of our own will. The early internet became a gathering space for waves of magically inclined cybernauts. Technopagans, Discordians (essentially: worshippers of disorder), neopagans, Wiccans, transhumanists could find each other in cyberspace, shoring up the notion that digital life itself might presage the magician’s eschatological dream of a place where human creativity could shape the landscape of its world.

The mystical algorithm presents us with a landscape in which our desires determine all that we see

In the 1990s, the Extropian transhumanist Max More hailed the internet as an evolutionary portal. ‘When technology allows us to reconstitute ourselves physiologically, genetically, and neurologically,’ he wrote, ‘we who have become transhuman will be primed to transform ourselves into posthumans – persons of unprecedented physical, intellectual, and psychological capacity, self-programming, potentially immortal, unlimited individuals.’ (More was explicit about the occult genesis of the Extropian movement, exhorting readers to praise Lucifer as a self-divinising rebel against a hierarchical creator-God.) The British philosopher Nick Land, later a major figure in the far-Right Dark Enlightenment scene, hoped that digital advancements would ‘accelerate’ capitalism and technological progress and precipitate a civilisational collapse that would hasten the post-apocalyptic world to come. A devotee of Crowley, Land moved into the magician’s former home after resigning from the University of Warwick. He also coined the portmanteau term ‘hyperstition’ (‘hyper’ plus ‘superstition’) to express the notion that an idea might become real merely by being thought, which sounds uncannily like a precursor of manifesting. Later waves of transhumanists include the philosopher David Pearce, whose World Transhumanist Association (later Humanity+) openly pursued ‘eternal life’. In an interview in 2007, Pearce said that, in order to do so, ‘we’ll need to rewrite our bug-ridden genetic code and become god-like.’

The internet has absorbed some of its techno-utopian luminaries’ foundational ideas to the extent that they are practically built-in. In some ways, it’s provided us with nothing more nor less than a magical canvas – a soul-space, to paraphrase the early internet historian Margaret Wertheim, where our desires, impressions and the forces that act upon them can be made ‘manifest’. In this shared collective hallucination, we can don ideal avatars, create untethered social and even erotic relationships, curate our self-image, and in turn allow the mystical algorithm to present us with a landscape – from news headlines to targeted advertisements – in which our desires determine all that we see.

In the modern internet, desire is the secret undercurrent shaping our new reality. Our desire for dopamine hits – Likes, hearts, a few seconds’ TikTok entertainment – is inextricable from the wider economic enmeshment of desire within a capitalistic attention economy, where our time and clicks are monetised in the service of advertisers bent on stoking our desire further. Unencumbered by our bodies, or communities, we live in a miasma of yearning, willingly succumbing to an increasingly palpable form of spellcraft practised by the digital magi who profit from our attention. Like the old witches’ bargains of eras past, we agree to sell parts of ourselves – our eyeballs – in exchange for certain illusory fulfilments of desire packaged up by powerful corporate tech titans and memetically gifted shitposters capable of ‘going viral’ with a perfectly worded image or tweet. Memes, in this telling, become the modern interpretations of the magician’s sigil: a magical image empowered to convey the magician’s desired energy.

Charged with the collective energy of each subsequent re-Tweet or repost, memes seep into our subconscious and influence what we think, how we act and who we vote for. Memes, like sigils, are replicated in the digital space, first through the mage’s ability to tap into our desires, marionetting us to Like and re-Tweet, then through our collective urge to add meme power to our own personal brand. And, by channelling our desire and rearranging our interior landscape through a clever working of our cybernetic geography, the digital magi have the very power over us that so fascinated Crowley and the chaos magicians.

But has the internet betrayed the more idealistic principles of its early engineers, for whom human transcendence was a more collective proposition? Has the power of the few able to look behind the curtain replaced the goal of shared human liberation? Perhaps to a degree, but even in these more seemingly humanistic visions of internet culture, we find a chilling nihilism: a sense that magic is fundamentally about controlling other people’s perceptions. Speaking about the magic of being online, an early internet user, going by the handle legba, told Davis:

Words shape everything there, and are, at the same time, little bits of light, pure ideas, packets in no-space transferring everywhere with incredible speed. If you regard magic in the literal sense of influencing the universe according to the will of the magician, then simply being [online] is magic.

Put another way, digital ‘reality’ takes the magical principles of energy manipulation as its architecture.

We are all caught up in the cult of Hermes, or Prometheus, or Lucifer, in which the secret truth revealed by transgression is that truth is only ever a fiction of fools: reality is only ever what you can make people believe. Our social lives, sexual lives, professional successes are all mediated, in part or in full, by a disembodied landscape that quite literally runs on the engine of desire. The hypercapitalist attention economy – which invites us to post pictures of ourselves for Likes, or tell compelling stories about ourselves for GoFundMes or Kickstarters, or turn our eyeballs to clickbait that, in turn, shows us advertisements for items on Etsy or Amazon that we’ve already been craving – doubles as a kind of manifestation of the principles of post-Crowley magick. It is desire that makes reality real. It’s hardly surprising that new spiritual movements have cropped up in this postmodern landscape – from Left-coded practices like WitchTok to the ‘meme magic’ of the 2016-era alt-Right. Reanimating esoteric ideas of self-divinisation, and harnessing ‘energy’ to ‘manifest’ reality by attending to and valorising our own desires, they insist that what we want makes us who we are.

The spiritualised space of the internet has made magicians of us all in the service of becoming our best selves

As such, modern internet culture seems more indebted to Crowley’s nihilism than to the promise of Hermes Trismegistus. Widespread disinformation, ‘engagement farming’, meme culture, Russian troll bots and other fragmented attempts at capturing and shaping our attention function like magic spells of their own, warping our perceptions to reflect the perceptions of those who wield the memes. You might say the ‘meme magicians’ have won. They have revealed, at last, the dark heart at the centre of Pico’s seemingly optimistic vision of humanity: that, when we fashion ourselves according to our desire, it is because there is nothing real, or meaningful, in this world except those desires.

Scottish witches of the 18th century had a word for this: glamour – appearing to others the way we wish to be, so we might impress upon them that which we wish to impress. By 2019, the concept of glamour magick was sufficiently mainstream for Teen Vogue to publish a guide to the practice, extolling teenage girls to ‘be a better you’. But, in 2023, we’re all doing ‘glamour magick’ – intentionally or not. Our participation in the spiritualised space of the internet, where energy, intention and vibes are indistinguishable from the memes and bots and Tweets and deepfakes that shape our collective consciousness, has made would-be magicians of us all in the service of becoming our best selves.

As more and more of our online lives play out on platforms owned or controlled by billionaires convinced of their own divinity, we may find ourselves less mages than fodder for other magicians’ wills. More troublingly, many of us don’t seem to mind – or, if we do, we don’t mind quite enough to disenchant ourselves. We just keep pressing, playing, Liking and sharing. A Crowley devotee might think that this is because we are, after all, sheeple, lacking the mage-like temperament to determine our own destinies, or that of others. A more charitable read is that desire itself is asymptotic: it is never fully fulfilled. The longing for what we cannot have, for being more than we are, is as endemic to the human condition as death. The lure of the internet lies in the promise that this click, this article, this purchase will at last result in the final consummation we crave. We will be seen, paid attention to, and perhaps even loved, in just the way we wish to be. It is a promise as palpable as Eve’s apple.