Suppose that error could be abolished. What would someone who never makes a mistake be like? There are two very different responses to this question. One is to think of a superhuman, god-like being. The poet Alexander Pope’s line – ‘To err is human; to forgive, divine’ – is based on that thought. God might pardon but He cannot Himself make mistakes. Infallibility would seem to go hand in hand with omniscience and infinite wisdom.

The other possibility is an entity that, far from superhuman, is largely unthinking. In the 1990s, the comedian Bill Hicks would accuse particularly slow-witted audience members of staring at him like ‘a dog that’s been shown a card trick’. At one level, this lovely image calls to mind a hapless showman wasting his craft on an uncomprehending creature. Hicks was, in part, being self-deprecating. Only a sucker would get drawn into such a futile task. But the implied criticism of his audience is more devastating. For it invokes a whole domain of stupidity beyond that of being a sucker.

The whole point of watching a magic trick, after all, is to be duped. But to be deceived, you have to form an understanding in the first place. The audience has to suppose, albeit wrongly, that, say, the Ten of Hearts was in fact shuffled back into the deck. The proverbial dog has no such apprehensions. It will just ignore what it perceives as meaningless markings on bits of cardboard. Hence it is immune to deception. The same goes for my audience, Hicks is saying: they lack the wits even to follow – and so to fall for – the set-ups to his gags. Susceptibility to error validates rather than detracts from rationality.

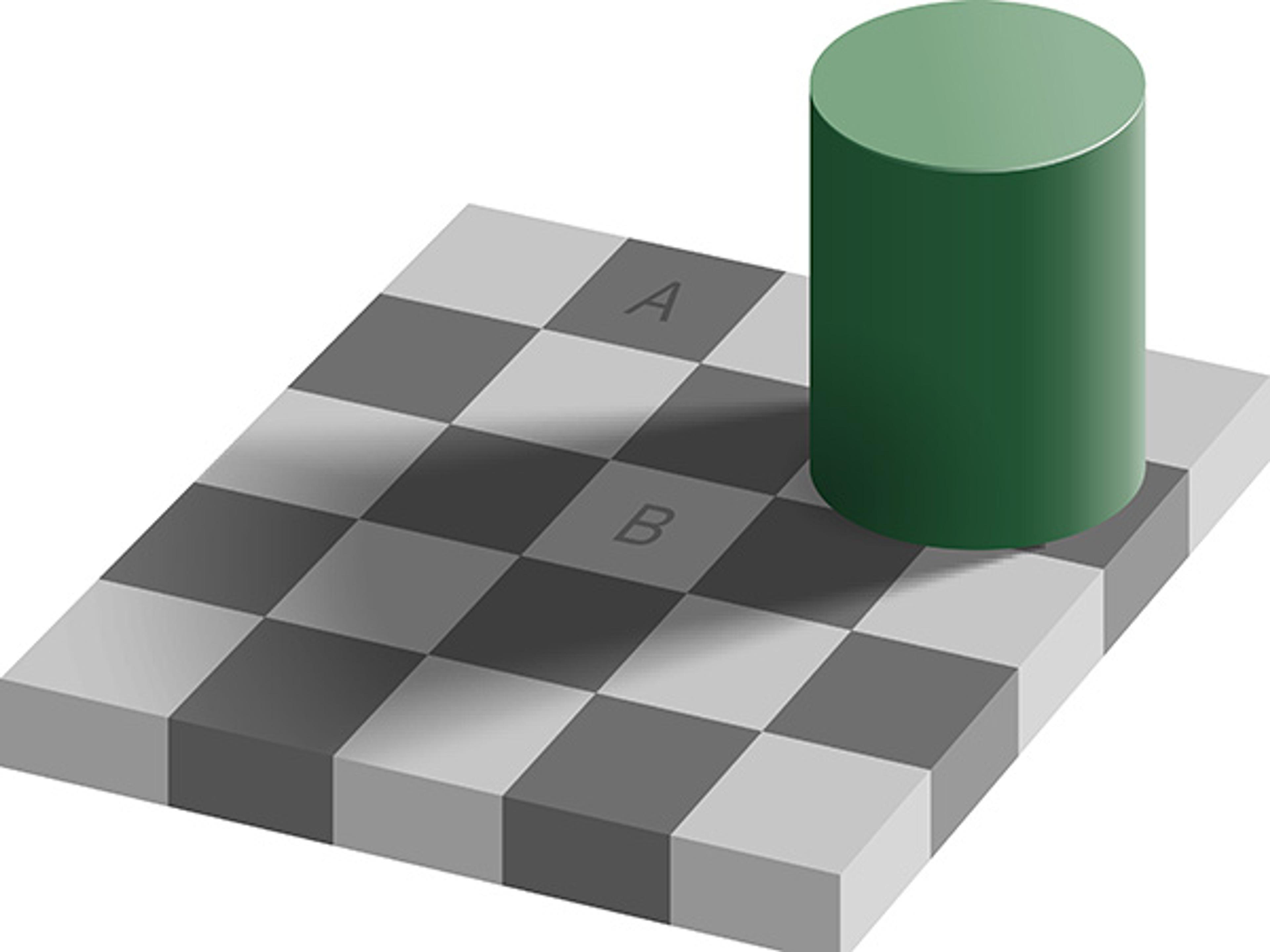

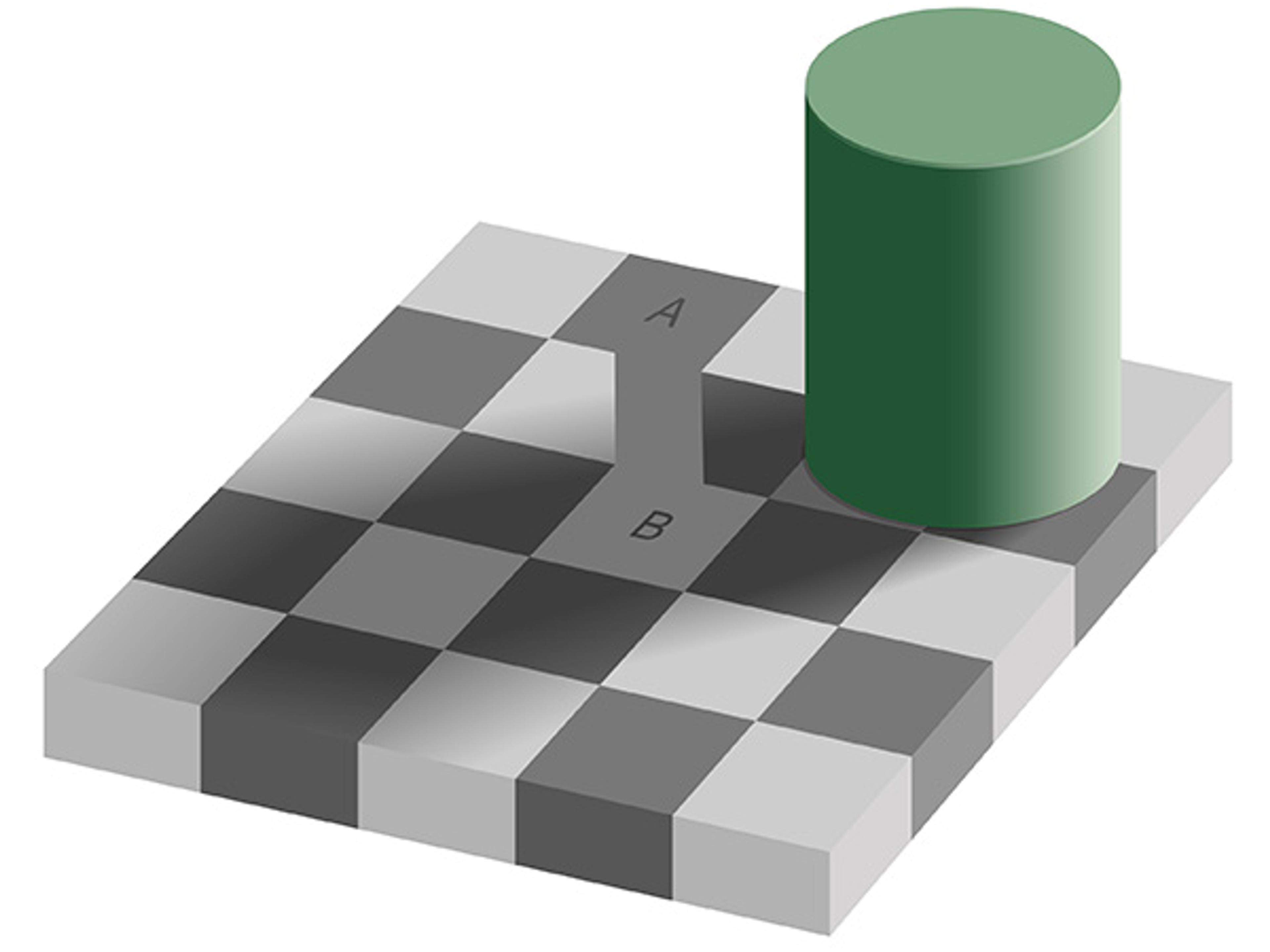

Those who study the human visual system also draw a link between the capacity for error and the capacity for thought. Consider the following illusion, created by the neuroscientist Edward Adelson at MIT, which involves a cylinder casting a shadow on a checkerboard. Square B, under the shadow, appears lighter than Square A. Yet the pixel shade is in fact exactly the same.

The illusion arises because the brain makes inferences about objects under shadow and compensates accordingly. Imagine looking at a real checkerboard, as opposed to a picture: the white squares under shadow would – just as your brain tells you – be lighter than the black squares outside the shade. As Adelson comments: ‘As with many so-called illusions, this effect really demonstrates the success rather than the failure of the visual system.’ That your brain occasionally makes this kind of mistake is testament to the fact that it is doing complex, intelligent things that go beyond merely absorbing incoming sensory data.

The antithesis of the view that normal, intelligent people are susceptible to error is a view that treats people as infallible. There is a strand of contemporary thought that holds that people should indeed treat one another – and themselves – as being, in effect, incapable of error in a wide range of matters, ranging from day-to-day decisions about how we spend our money to ideological commitments. I call this a belief in ‘general infallibility’ – general because it is supposed to apply not just to certain authority figures but to everyone. This view is urged upon us, we will shortly see, by certain influential ideas arising out of mid-20th-century sociology and economics – ideas that appeal to people of a broad spectrum of political opinion, from those who hold egalitarian commitments to those with hard-nosed, free-market ideals.

General infallibility is a tempting proposition. Treating an individual’s attitudes and preferences as givens – as matters beyond debate or criticism – might seem to promote human dignity by forcing us to treat all views as equally worthy of respect. But such an outlook is likely, if anything, to have the opposite effect. This is because taking seriously a person’s capacity to make mistakes is critical to taking seriously their capacity for rationality. Only by recognising that people are capable of error can we properly value anyone’s goals or engage in rational debate.

The term ‘infallibility’ is most often associated with the Roman Catholic doctrine of papal infallibility. That form of infallibility applies, obviously enough, only to one person. It is carefully circumscribed in other respects too. Catholics are free to think that the Pope has got it wrong in, say, his choice of attire or when he comments on something in the news. Only when he invokes his authority to lay down the law about religious doctrine does the concept bite. Another familiar form of infallibility, that claimed by totalitarian leaders, is not so limited. The worst tyrants demand not just to be obeyed but to be treated as incapable of error in every deed and saying. To that end, Stalin’s propagandists sought to falsify the historical record – with an airbrush if necessary.

General infallibility is a modern, democratised version of the infallibility traditionally claimed by religious and authoritarian leaders. Although, unlike those other forms of infallibility, it applies to everyone, like papal infallibility it has some bounds. Everyone agrees that errors can occur where others are very immediately affected. No one would suggest that those giving medical advice or, say, forecasting the weather, can never make mistakes. Yet, today, it is a quite prevalent view that it’s wrong to regard others as mistaken in their tastes and purchasing patterns.

Liberalism has long held that each of us should be regarded as, in effect, sovereign – ultimately entitled to choose – in our political, consumer and religious preferences. The doctrine I am highlighting is different. It goes further: it says that each person is not merely sovereign but free from error in those preferences.

Let’s be clear about that difference. The proposition that elections should determine, directly or indirectly, what action the government takes is pretty much inherent in the idea of democracy. But it is not inherent in democracy that elections should end discussion of the policies voted upon. Political liberalism does not justify forestalling debate, nor does it justify the habit that certain politicians have of presenting polling data as if it were an argument in itself for the merits of a position (the ad populum fallacy) – but such an approach makes perfect sense if something like general infallibility holds. Similarly, there is a difference between believing that music and books should be free from censorship on grounds of taste (as liberalism urges) and believing that no one ought to pass comment on anyone else’s taste (as general infallibility implies). The latter opinion finds expression in the view – in a world of online ratings and ‘likes’ – that there is something inherently snobbish about professional arts criticism.

Why not think that whatever is right for an individual is whatever that individual regards as right?

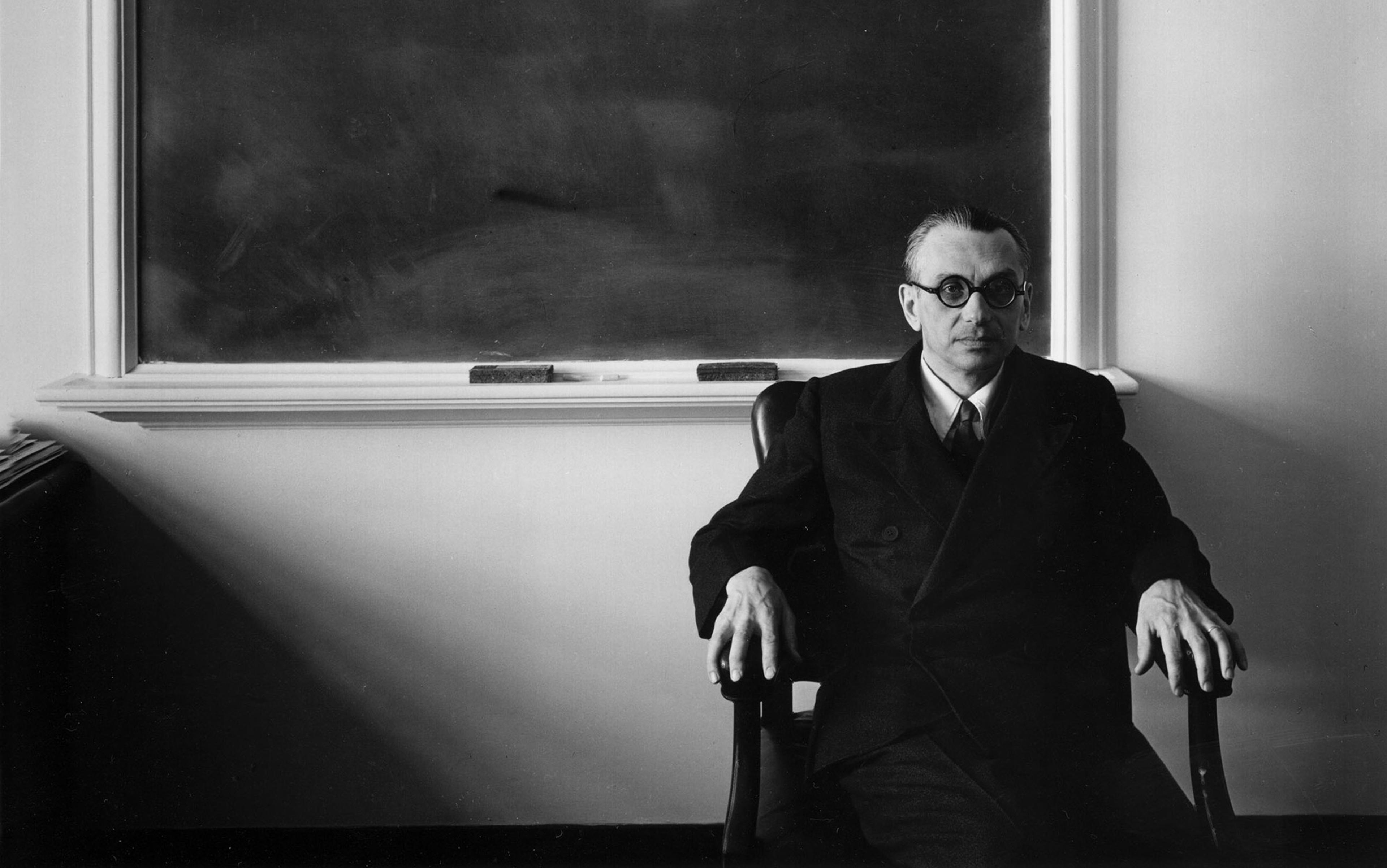

How did the notion of general infallibility arise? One likely source is cultural relativism. This has its origins in the development of anthropology as an organised discipline in the 19th and early 20th centuries. There was then a growing realisation of the problem of ethnocentrism – the tendency of people, anthropologists included, to view other, unfamiliar cultures through the lens of their own – and to misunderstand them as a result. The antidote recommended by the pioneers of modern anthropology such as Franz Boas and William Graham Sumner was essentially a dose of humility. In studying, say, the marriage customs of Samoans you must consider these in the context of Samoan society and not interpose Western conceptions of what marriage involves. Moreover, you must avoid passing moral judgment, since this can only interfere with accurate, dispassionate study. These sensible precautions, now considered basic axioms of the discipline, are purely methodological. They describe how such research should be done but not how the world is, nor what is right or wrong.

The rhetoric sometimes went further. The American anthropologist Ruth Benedict declared in 1934:

We do not any longer make the mistake of deriving the morality of our locality and decade directly from the inevitable constitution of human nature … We recognise that morality differs in every society, and is a convenient term for socially approved habits. Mankind has always preferred to say, ‘It is morally good,’ rather than ‘It is habitual,’… But historically the two phrases are synonymous.

This relativistic claim – that one society’s morality is as good as another’s – entered wider discourse in the mid-20th century via the pronouncements of Benedict and those of her colleagues. This is despite the fact that anthropologists soon started to disavow such an extreme position, retreating to more modest, purely methodological cautions about heeding cultural contexts. (As the philosopher John Tilley pointed out in 2000: ‘The view that relativism is an axiom of anthropology is either false or 50 years out of date.’)

Cultural relativism is open to this obvious objection: if what is right for a society is whatever that society regards as right, why not go one step further and think that whatever is right for an individual is whatever that individual regards as right? But then, of course, you might be persuaded to take just such a step. After all, it is a logical one. If so, you end up convinced that nobody can be mistaken about anything.

Claims that the subjective beliefs of individuals must be treated as infallible also provoke much criticism. Unfortunately, a common, almost reflexive, response is to insist that some people have better credentials to be taken seriously than others, whether because of differences in educational attainment, intelligence or moral fibre. This is a poor move. It smells of chauvinism. It also betrays a lack of commitment to rational discourse, since it proposes that ad hominem considerations – the characteristics of the speaker – should pre-empt listening to and assessing the evidence and argument put before us.

There is a better way of responding to relativism, one that avoids indulging in the predilection we seem to have as social animals for exercises in ranking one another. We can notice that our own beliefs and attitudes can change. According to the British Social Attitudes survey, in 1983 only 17 per cent of adults in the UK thought that same-sex relationships were ‘not wrong at all’. In 2016, the percentage had risen to 64 per cent – a vast shift. It is hard for a relativist to account for such changes. If people are sometimes amenable to persuasion – however infrequently – then it cannot be the whole story that they hold the particular basket of attitudes they do simply because that’s what they think.

Another prop for general infallibility has a quite different source. This is the concept of ‘revealed preference’, a foundational idea in modern economic thinking, pioneered by the influential 20th-century American economist Paul Samuelson. This idea was even more radical than relativism. If relativism proposes that you cannot question the choices of others, we will shortly see that Samuelson’s theory implies that you cannot treat even your own choices as mistaken.

Samuelson’s theory has its roots in the efforts of economists and political scientists to pin down the notion of ‘preference’. A well-functioning society should, it has long been supposed, satisfy the desires of its members as much as possible. But how do you tell how well or badly a society is succeeding in that respect – how are desires to be measured?

The prevailing intellectual fashion in the first half of the 20th century was to avoid questions about how people thought or felt. It was regarded as unscientific to presume to peer into the mind. Psychological questions were to be settled by observing how individuals responded to stimuli, without speculating about underlying mental processes. This approach came to be termed ‘behaviourism’. Researchers were supposed to look to how people behaved, not what might be happening inside their heads. But surely the notion of a ‘preference’ is inescapably connected with what happens inside the head? If you were a behaviourist and wanted to study preferences, you had, it seemed, a problem.

Samuelson’s solution was ingenious. Why not equate preferences with what people spend their money on? I give you $100. If you spend $30 on a restaurant meal, $50 on some jeans and the remaining $20 on a taxi home, I have learned what things you wanted and in which precise proportions.

As Samuelson wrote in 1948: ‘the individual guinea-pig, by his market behaviour, reveals his preference pattern’. Sure, you could get people to fill in questionnaires asking them to rate out of 10 how strongly they desire to eat a steak and so on. But this would give rise to tricky questions of interpretation (how exactly does a ‘7’ weigh against an ‘8’?), and of veracity (can you really trust people to give accurate responses in a survey?) Equating preferences with purchasing decisions dissolves such problems. Put your money where your mouth is and, behold, your true wishes are revealed.

If you want to buy crack cocaine, a disappointing book or a too-large microwave, all those things are rational

This idea has proved enormously influential. Its strength lies in its simplicity. One starts by assuming that each individual has a set of preferences – a utility function – whose maximisation will make that person better-off. Economists can then aggregate those functions and calculate the effect of changes in the relative cost of goods or varying budgets. Those calculations can be performed without passing judgment on anyone’s underlying preferences. (It helped too that Samuelson wrote one of the subject’s leading textbooks, as he himself appreciated: ‘I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws – or crafts its advanced treaties – if I can write its economics textbooks.’)

Yet there is something odd about the idea of revealed preference. Taken seriously, it would make it senseless to pass judgment on even one’s own choices.

Suppose I spend $100 on a new microwave. I take it out of the box, carry it into the kitchen… and realise it doesn’t fit where I planned to put it. Perhaps I didn’t measure the space right. Or perhaps the dimensions stated on the box were misleading. Either way, I am not happy. I regret my purchase. But according to Samuelson’s theory, there is no reason for me to be regretful. When I parted with the $100 I thereby ‘revealed’ my true preferences. If they turned out to be for a microwave that doesn’t fit in my kitchen, well, then, at some level that is what I really wanted all along.

If our true preferences are always ‘revealed’ by our choices, regret never makes any sense. Yet regret is a very real part of life. I put this to an economist friend, a committed Samuelsonian. His response is to point out that preferences can change. Yesterday I wanted this microwave, today I would prefer a different model. But is that an adequate description of the situation? I think not. My objective all along was to buy a microwave for my kitchen. That objective never changed. If someone had told me that what I was about to purchase was too big, I would not have bought it. The painful mismatch between my goal and the choice I made makes me sorry.

What has gone wrong with a theory that does not allow people to have regrets? One idea is that economics assumes that humans are more rational than they really are. Our emotional life cannot possibly be captured, it is said, by the economist’s model of agents coldly calculating how to maximise their utility. We are creatures of emotional impulse – love, fear, hope – not just of calculation.

But that particular criticism is based, I think, on a misunderstanding. Utility maximisation is often described as a theory about ‘rational’ agents. Because of this it is often read as involving a claim about human nature, namely that people choose sensible, wisely considered things. Yet ‘rational’ in the particular sense implied by the idea of revealed preference has nothing to do with wisdom. If you tell my Samuelsonian friend that the theory fails to account for the irrational nature of humanity, he will retort that the concept of ‘irrationality’ is meaningless. And indeed it is, in a Samuelsonian world. For modern economists, what is ‘rational’ for a given person is more or less whatever that person wants. If someone wants to buy crack cocaine, a disappointing book or a too-large microwave, all those things are rational. If she is willing to spend her money on these things, those are her preferences.

Properly understood, modern economic theory doesn’t assume that we are unemotional, calculating or wise individuals, nor does it privilege those lucky enough to have such characteristics. Far from it. It deems whatever consumers want to be valid, no matter how damaging, how regret-inducing. In short, it has at its heart a very strong assumption of general infallibility. It assumes that we can never be mistaken about any decision, whether it be the result of careful deliberation or otherwise, whether it advances our goals or hinders them.

It turns out that the usual criticism of economic doctrine gets it the wrong way around. People are not less rational than it supposes but considerably more so – at least if ‘rational’ means having reasons for what you do. Having reasons makes you error-prone.

Consider how behind each decision we make, large or small, there typically stretches a large landscape of beliefs, plans and objectives. By buying a microwave, perhaps I am looking to avoid cooking. That objective might, in turn, depend on my doubting that I will ever learn to cook properly. That assumption might depend, in turn, on whether cooking is a skill that I think people ought to invest time in learning, which might depend on various preconceptions about the importance of learning new skills… and so on.

The idea of revealed preference insists that none of that background matters. What counts is fulfilment of your ultimate preference to buy this model rather than that, to take this job rather than that one. All that matters, in a world of infallible people, is the final choice. Yet the thus-overlooked hinterland of non-final preferences is filled with all of our goals, ambitions, values: the very things that matter most to us.

A person whose choices can never be mistaken cannot really have any meaningful plans, only impulses

Goals are intimately connected to the possibility of error. Goals tend to form nested hierarchies. I want this gadget because it has a low-energy rating – important because I believe it will cause lower emissions, important because I believe emissions harm the planet. Crucially, each objective is contingent on it advancing the objective it answers to in the hierarchy above it. If it transpires that low-energy-rated goods don’t, for some reason, actually help cut emissions, I will regard myself as mistaken in having bought them.

Similarly, while the vision system works by collecting information about the quantity of light hitting our eyes, that is not its ultimate goal: the objective is, rather, to represent the world around us as it is. Consequently the brain is happy to disregard some of the raw information fed to it from our retinal cells when the context indicates that such information is likely to be misleading – even if, as we have seen, this sometimes leaves us susceptible to optical illusions.

A goal is distinct from a mere impulse in the following way: a goal can potentially render other preferences mistaken. Impulses cannot. Your impulse to stay at a party cannot be ‘mistaken’ simply because you have a competing impulse to call it a night. But staying out might be a mistake if there is an objective informing your desire to go to bed, such as your plan to attend a meeting the next morning. A person whose choices can never be mistaken cannot really have any meaningful plans or objectives, only a series of impulses.

What’s more, the fact that some of our preferences are contingent on others – and so can be mistaken – is what allows people to persuade one another. If you and I realise that we share some goal, say, of reducing traffic accidents, you can seek to reason with me that my immediate preference in the matter – to vote for a particular policy with that objective in mind – is mistaken because it will not achieve that goal. If, instead, you believe that my inclination to vote for that policy is an inscrutable facet of my identity – it is my preference, and that is the end of the matter – persuasion is not open to you. Your only hope is to join forces with enough other like-minded people and then silently and grimly out-vote the likes of me.

General infallibility creates the illusion that people are essentially mindless. It holds that we believe what we believe, and value what we value, for no reason at all, or at least for reasons that are unintelligible to anyone else. Under those conditions, no one can engage with anyone else’s views or take them seriously. If, today, identities are becoming increasingly tribally defined, with each group living in its own ‘bubble’, this is an illusion that we urgently need to learn to see through.

To err is human. Missteps, misapprehensions, misspeakings, momentary lapses and mess-ups are part of the fabric of life. Yet we are capable of making mistakes precisely because we are thoughtful, intelligent beings with complex goals and sincerely held values. We wouldn’t be able to if we were otherwise. Regrets: we’ve had a few. But we are the wiser for them.