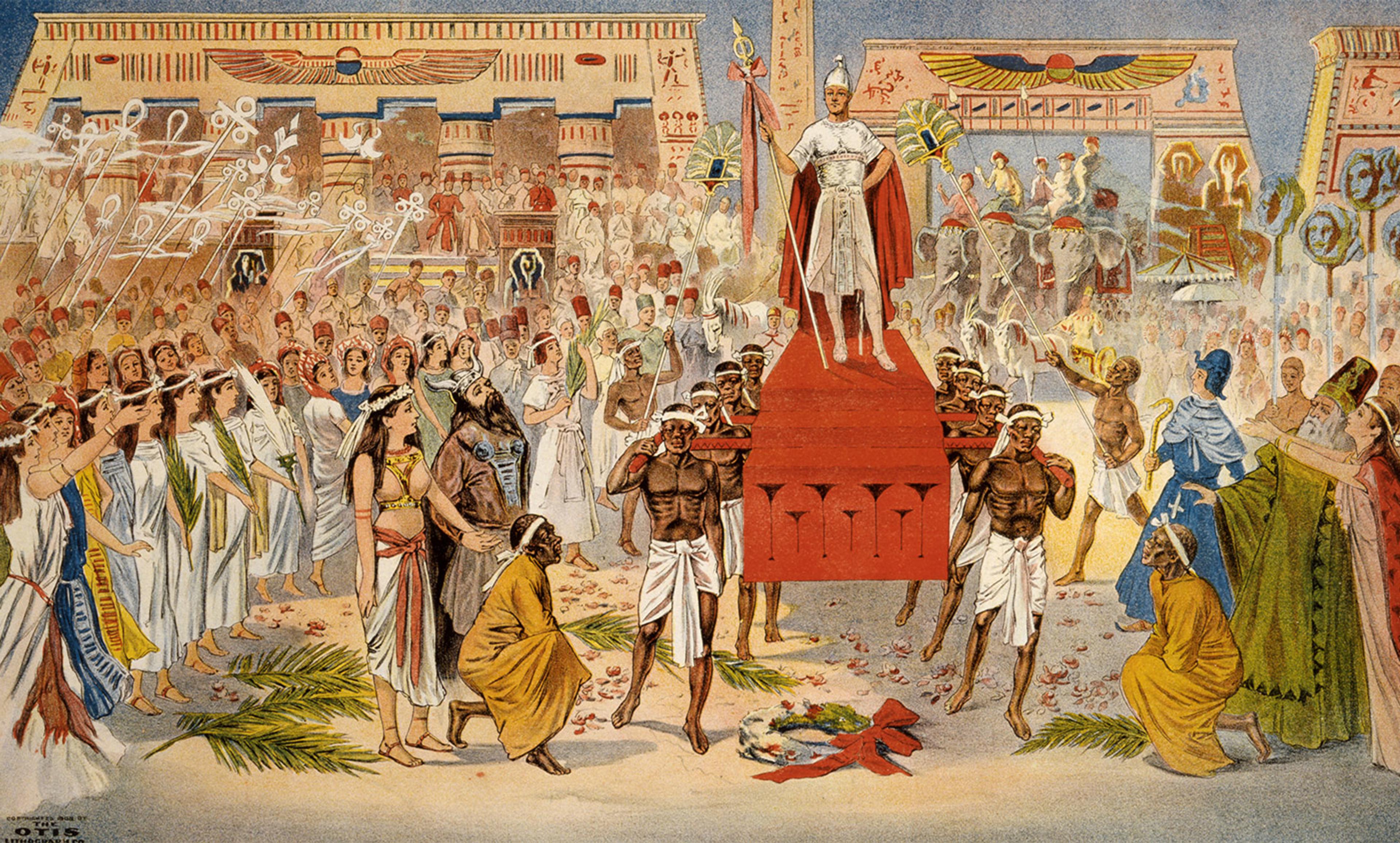

Verdi’s Aida premiered at the Khedivial Opera House, Cairo, to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

The new Royal Opera House Muscat in Oman and the brand new Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi revive vital questions. Are these new institutions instruments of Western domination, or are such cultural spaces compatible with Muslim social life? The theorist Edward Said argued that Cairo’s Khedivial Opera House was a folly and that Aida was a colonial opera. His book Culture and Imperialism (1993) very nearly equated European culture with European rule. Ever since, this idea about the cultural component of imperialism has played a dominant role in scholarship on empire. While a number of opera experts have since rejected the label of ‘colonial opera’, the idea of culture as a domain of imperialism and colonialism remains important in scholarship. Following Said’s logic, we should conclude that today’s new cultural institutions in the Gulf are representative of Western domination. But the question is an empirical one, and history tells us a more subtle and interesting story.

Egyptians call Cairo ‘the mother of the world’, and indeed in the 1860s and ’70s the description seemed apt. In these two decades, capital, technology and foreigners flowed into Cairo, and from Cairo across Egypt. The works of the Suez Canal, British-French competition, rich pashas and Ottoman intrigues all jammed together. In the midst of this exciting time, on a Sunday evening in February 1870, a young Muslim journalist, Muhammad Unsi, sat in the Khedivial Opera House. He was watching the Rossini opera Semiramis. He immediately grasped the connection between theatre, language and patriotism. ‘Oh, if such refined works were translated into Arabic successfully,’ Unsi wrote in a review of the performance, ‘and they were performed in the Egyptian theatres in the Arabic language as an innovation, that the taste [for theatre] may spread among the local groups. Because this is the sum of the patriotic components that facilitated the advancement of the European countries and helped to enhance their internal conditions.’

So, can the arrival of Western culture in the Middle East be equated simply with European imperialism? Is this how the European bourgeoisie, as Marx would say, ‘creates the world after its own image’? First, let us consider the question of power. The Khedivial Opera House and other new Western-style cultural spaces represented authority to ordinary people in the streets of Cairo. The intention of European states to enforce their economic interests on the Ottoman Empire, Egypt included, is also crystal clear throughout modern history: just look at the Suez Canal.

The danger in attributing ultimate change to Europe, though – be it military, cultural or technological – is that one might underestimate and, ultimately, deny local agency. Indeed, in 1860s Egypt, the opera house symbolised the power of the local Ottoman ruling elite. It was the governor Ismail Pasha, the local Muslim ruler, who ordered and paid for it – much before the 1882 British occupation of Egypt.

Second, the use of these cultural spaces by local intellectuals and ordinary people ultimately defines whose visions the performances embody. The social history of the institutions and the ideas that they stir shed more light on their ultimate function in society than does their founding moment.

True, followers of Said might also argue that, despite Unsi’s enthusiasm for opera (and, actually, also for ballet), he together with Ismail Pasha were elite proxies of Europeans. They had no real agency, and Unsi’s engagement with novel forms of self-expression was an illusion.

At first glance, what could better please the exotic, Western Orientalist imagination than a Muslim journalist watching an Italian opera in Cairo? We have to look deeper to avoid exoticism and discover whose power directs cultural processes.

Unsi was a passionate teacher of Arabic and an enterprising minor businessman who experimented in the booming printed-book market in Cairo in the 1860s. His father Abu al-Su‘ud was a translator in the service of the government and the editor of the journal in which Unsi’s review of Semiramis appeared. In 1872, Unsi teamed up with an Italian teacher and proposed to the government a drama school for young Egyptians. Meanwhile, James Sanua, a now-legendary Egyptian-Italian Jew, submitted a proposal for an ad-hoc Arabic theatre troupe. Neither of these rival projects came to fruition, not because of European colonialism but because Ismail Pasha was not interested, perhaps judging them too disturbing, too patriotic, too potentially political. This background shows our man, not in a blind fascination with elite European products, but as an active, confident agent of change who finally did not receive support from his own government.

Let us step outside the opera house. In contrast to Said, I prefer to understand ‘culture’ in a larger, messier, framework. The eastern Mediterranean was a cultural marketplace of entertainers: Arabs, Armenians, Turks, Italians, Greeks and French. Urban culture embodied various ways of spending free time, in theory strictly separated according to social class and gender: the songs of poor local and European workers, the quick satisfaction of vices by sailors and soldiers in pubs and brothels, the rich merchants’ salons and theatres, and the government’s Opera House in Cairo.

Technological inventions, especially increasingly cheap and fast Mediterranean steam ships, made both Italian, French and also Ottoman and Arab theatrical tours more possible by making it easier to move actors, singers, instruments and ideas across the sea. Culture is also business.

Due to this acceleration, in the late-19th century a hybrid Arabic and Turkish (and Greek, Armenian, French and Italian) cultural economy of musical theatre developed. Arabic music made European acting acceptable and contributed to the acceptance of the new performance genre. Arabic operetta developed in ‘low’ and ‘high’ versions that remain alive today even in official state revues, such as the one staged recently for the old-new military leaders of Egypt. Indeed, modern Arab political propaganda makes ample use of performance culture.

Culture in the 19th century was thus a multilevel social domain in which symbols and practices of leisure constantly circulated due to the new imperial technologies and routes. Within this frame, Unsi can be seen as only one active hub among the milliard buzzing connections. European domination, privileges and interests are still clear, as are hierarchies of power. But such a multiangled frame allows us to move past the bifurcated vision of East versus West, or colonised versus coloniser.

So, what should be the future of the Opera in Muscat, the Louvre in Abu Dhabi and other new art spaces in the Gulf? Let us learn from the example of Unsi. It is ultimately up to the local rulers to allow their citizens to possess the new buildings and forms of art, and allow them to transform these to their own taste and pleasure. Only in this way can culture stop functioning as domination.