There is a scene painted on a clay drinking cup by an artist called the Foundry Painter from the early 5th century BCE. True to the painter’s name, the outer surface of the cup (called a kylix in Ancient Greek) shows the interior of a bronze foundry, where metallurgists worked to cast statues and other objects. Two nearly finished statues are carefully attended to by the busy foundry workers. One statue has yet to be fitted with its head, which rests on the ground. The posture of the statue strongly suggests it will, when finished, depict an athlete. The second statue is an over-life-sized, triumphant, striding warrior, a brazen hero bristling with helmet, spear and shield.

Aside from the warrior’s armour, both statues are unclothed. And they are not the only ones: three of the smiths are likewise nude. Two nude smiths, one of whom crouches down to stoke the fire, are closely tending the furnace used to heat solid metal to molten form. The melting point for bronze is approximately 900°C – certainly a bold environment in which to work without protective clothing! The third nude smith is hard at work polishing the nether parts of the finished warrior statute. Other figures in the scene are wearing various sorts of clothing, a short cloth wrapped around the middle for the two clothed bronze-workers or a longer flowing cloak for two larger gentlemen who appear to be spectators at, or patrons of, the shop.

The scene raises many germane questions about Greek nudity. We can see right away that both statues produced by the foundry are naked, hinting at a situation in which the artistic convention for large-scale images of strong, heroic males may have been to depict them in a state of general undress. But does this art imitate life? That is to say, should the nudity of the athletic statue lead us to believe that, in ancient Greece, athletes competed totally naked? Should the nudity of the hero be taken as evidence that warriors really went to battle wearing nothing but their armour? Moreover, what explains the various states of dress and undress among the human figures in the scene? Why are some of the figures clothed, and others not? To understand this scene, and many thousands more in the vast corpus of Greco-Roman art, it is necessary to confront a clear truth: the nude male body was a powerful, all-pervasive, many-faceted symbol for the ancient Greeks.

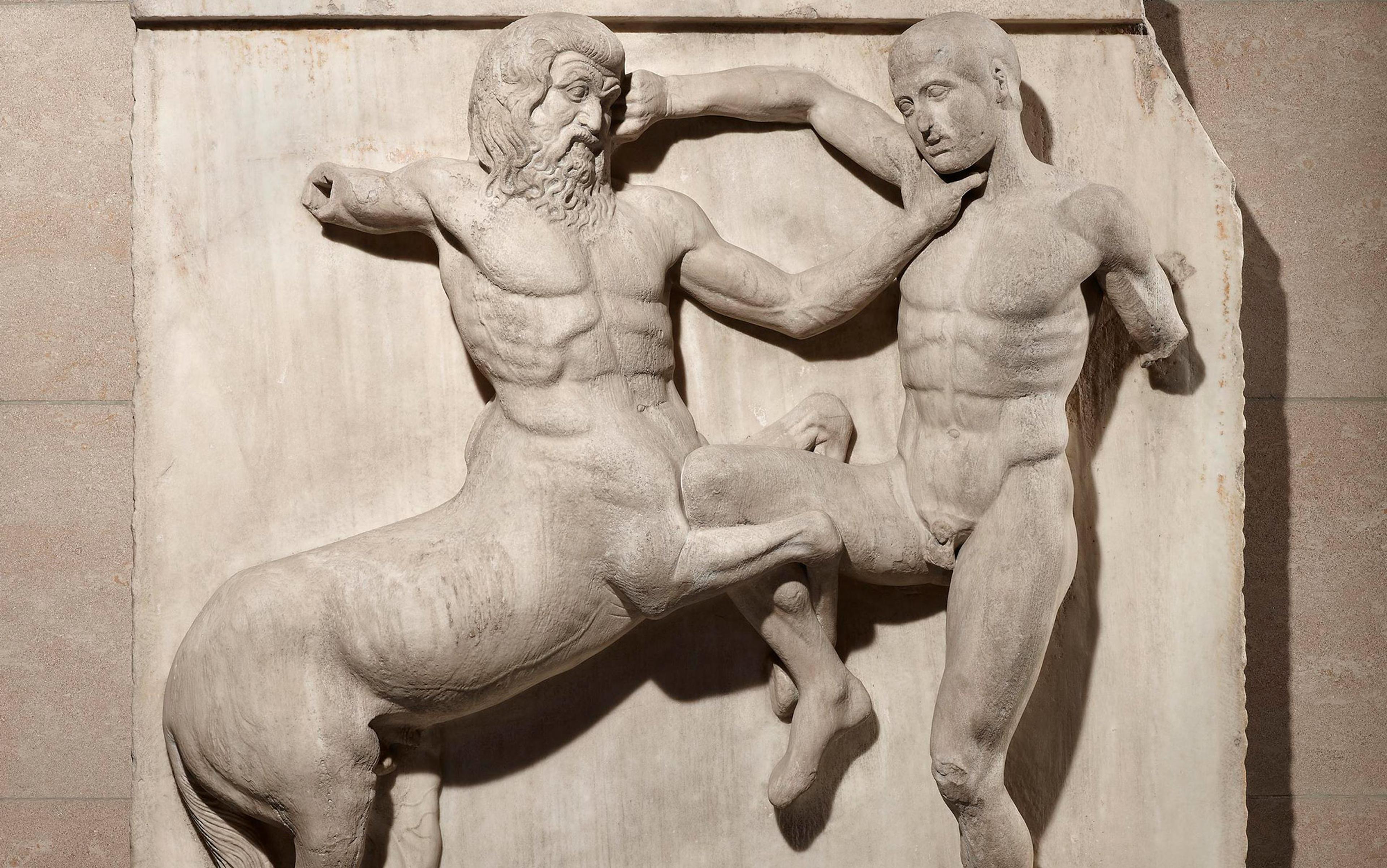

Scholars struggle to answer these questions with certainty. The truth is that male nudity, as both an aesthetic and a real practice in the ancient Greek context, was many-faceted. Men in Greek art seem to do pretty much everything without their pants on, ranging from the obvious (having sex), to the sensible (bathing and swimming), to the painful (riding horses), to the seemingly suicidal (fighting battles). The convention of nudity in Greek art cuts across apparent class differences as well as a wide range of activities: ‘working-class’ nude men harvest olives and dig clay for pottery production, while heroes and gods from Greek myths and legends fight battles, pursue paramours and mourn lost friends, all while clad in armour that curiously leaves their most sensitive bits exposed.

Black-figured amphora, attributed to the Antimenes Painter, depicting olive harvesting (520 BCE). Courtesy the British Museum

We can identify many different categories of nudity in Greek art. The normal and normative heroic and athletic Greek male is unaroused and poorly endowed, but the contemplative sophrosyne (Greek for ‘moderation and self-control’) of the heroic nude is quantitatively matched by plentiful erotic scenes that adorn Greek wine-drinking and wine-serving sets (as many tourists to modern Greece have discovered upon encountering decks of ‘naughty pottery’ playing cards on sale in the streets of Athens). These sexy vignettes were well suited to the context of elite drinking parties where affairs often veered toward rowdiness and raunchiness as the evening progressed. The darker, uncontrollable side of Greek erotic desire is also expressed in the guise of ithyphallic satyrs (a male nature spirit with the ears and tail of a horse, and a permanent erection) cavorting in drunken pursuit of sexual prey amid richly conceived scenes of Dionysiac revelry.

An ithyphallic satyr (c200-50 BCE). Courtesy the MFA Boston

Greeks saw the uncontrolled, erect phallus as a source of fearsome power. This is most evident in the widespread presence at crossroads in Athens of ithyphallic pillars topped by the head of Hermes. These strange monuments were called herms. They were thought to have an apotropaic (‘danger-averting’) quality, serving to ward off demons and other ill portents that were especially prevalent where paths crossed. In one of the more bizarre and amusing episodes of Athenian history, the frattish playboy Alcibiades was accused of smashing the penises from these herms while on a bender with his entourage. This horrific act of sacrilege was seen as such a disastrous affront to the gods of the city that it was cause for a criminal investigation and Alcibiades’ recall from his generalship of an important military expedition.

The fearsome, fertile power of human reproductive parts was widely appreciated

The Classics scholar Eva Keuls entitled her book on Greek culture The Reign of the Phallus (1985), an apt turn of phrase to describe the heavily and kaleidoscopically phallic visual culture that people wandering around ancient Athens would have encountered. Overall, it is clear from the Greek case that the undressed human body can and did convey many things, depending on the context. Most of the nudity in Greek art probably does not actually represent life. We are fairly confident that Greek soldiers did not go to battle naked, that craftspeople did not in fact operate their kilns without protective clothing, and that farmers did not follow the ploughshare and oxen through cloddy fields in their birthday suits. That is to say, ancient Greece was definitively not a nudist society.

Indeed, many forms of nudity prevalent in Greek art are fairly conventional in human systems of thought and art. Nudity is often used as shorthand for ‘dead’ or ‘defeated’ in art from Eastern Mediterranean societies, where casualties of war or captives destined for execution most commonly appear unclothed. This convention is occasionally present in Greek evidence, too. The Iliad speaks with vivid horror about dogs and birds feasting on the exposed bodies of the dead, and a few early Greek vases show birds gnawing on the exposed groins of vanquished warriors. If the human subject is depicted as naked, it’s a good bet that that human is no longer alive, or soon won’t be. In addition to the dead or the doomed, divine figures like gods and heroes appear nude in many ancient artistic traditions, and apotropaic nudity is not uncommon in other contexts: the fearsome, fertile power of human reproductive parts and the powerful urges with which they are associated seem to have been widely appreciated as human forces to be reckoned with. Erotic nudity, moreover, is the norm wherever scenes of carnal lust form a part of popular culture.

However, there is one form of nudity in Greek art that is quintessentially Greek and that does reflect a real and distinctive real-life practice. This is what the great, late art historian and Etruscologist Larissa Bonfante termed ‘civic nudity’, in what remains a key paper on the topic from 1989. Bonfante described civic nudity as informal, nude athletic activity that took place on a regular basis in gymnasia.

Understanding the institution of civic nudity is crucial for reconstructing the central place of the naked, young, athletic male physique as a Greek cultural ideal, so here it is worth unpacking some of the details. There are three points that should be emphasised. The first is that only citizens of a certain socioeconomic class were able and encouraged to become athletes. The second is that athletes were – in life as in art – naked throughout both training and competition. The third is that naked athletic training in the gym had an overtly erotic character. It turns out that these three points are rather intimately connected to one another, but we can begin by treating each on its own.

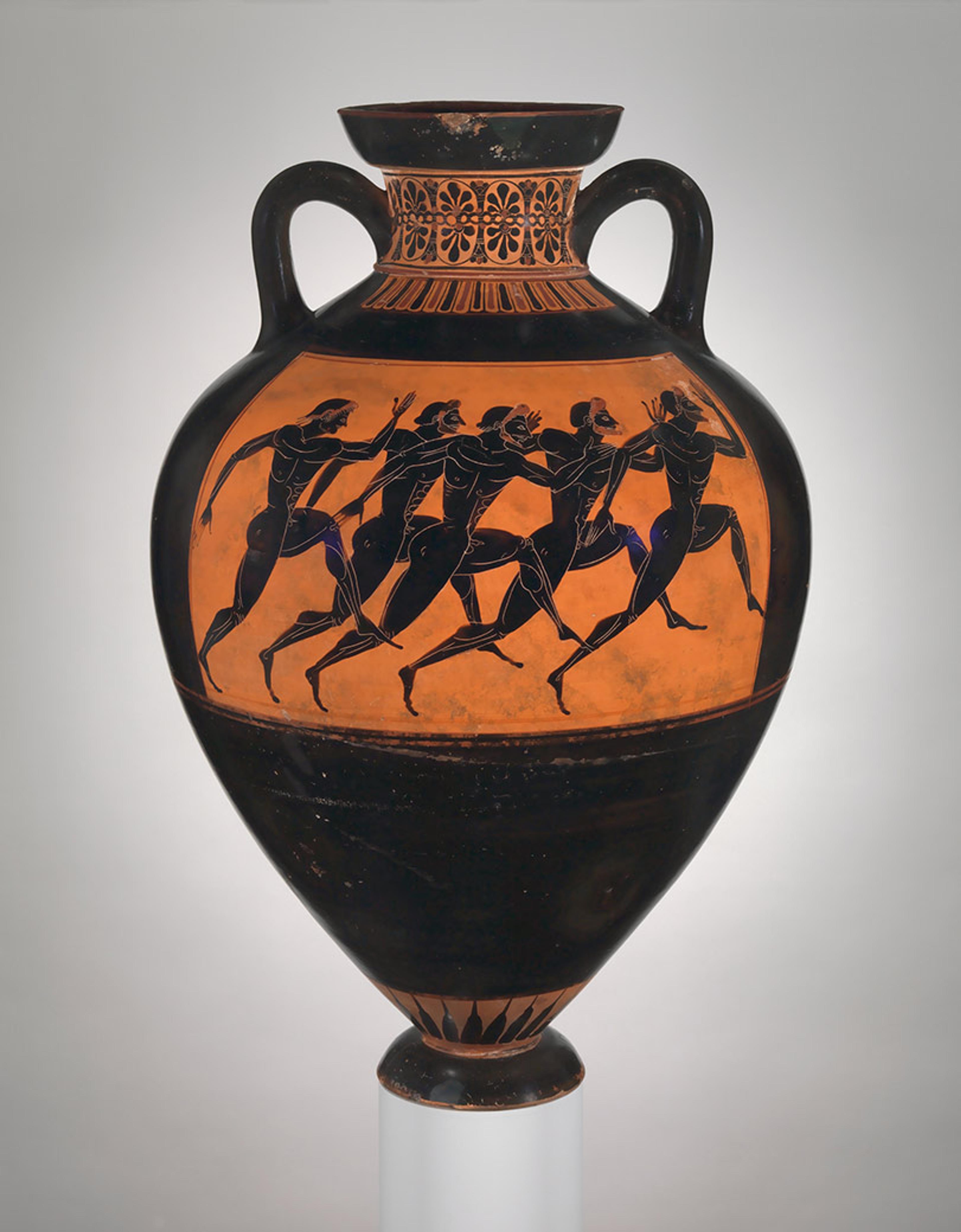

Sports, including running, wrestling, throwing and horse-racing, were very popular in ancient Greece, and competitions of all kinds highlighted festivals throughout the Greek world, including major events like the ancient Olympics and innumerable local games organised within and for smaller communities. Despite the wide popularity of sport, access to participation in athletics was formally circumscribed to a small portion of the population.

We are used to thinking of athletics as a levelling force in society, the ultimate meritocratic arena wherein anyone, regardless of class or wealth, can run, throw, hit and sweat their way to fame and fortune as professional athletes. Youth sport is widespread in most modern developed societies, and mandatory gym classes provide a path to physical training and development across the socioeconomic spectrum. This state of affairs is dramatically different from the ancient Greek situation. Only Greek male citizens could train and compete in sports.

Within this population, informal constraints limited participation even further. Most poorer Greeks operated close to a basic subsistence level and worked on small farms, so they did not have leisure time available for long training sessions in the gym, located far off in the city centres, let alone could they take months out of their schedule to train and compete at Olympia without incurring disastrous agricultural consequences at home. This means that vast swaths of people who lived in an ancient Greek city – women, local residents who were not born in Greece, foreigners, and poor men – were largely excluded from athletics. In turn, participation in sport was strongly emblematic of a certain political and socioeconomic in-group – relatively wealthy, Greek, citizen males.

The Greeks themselves had little clear idea of how and why athletic nudity emerged

I now turn to the second key point, the cultural convention of athletic nudity. Athletes in ancient Greece were always expected to both train and compete naked. In fact, our modern word ‘gymnasium’ comes from the ancient Greek word gymnos, an adjective that means ‘naked’. Thus, while we don’t honour its etymology any more, the word’s original meaning was literally ‘naked place’.

Why nude athletics? Answers to this question are elusive. Although many texts from the classical world survive, they have little to say about the meaning of nudity in society or art. The textual sources that do touch briefly on naked sport indicate that the Greeks themselves had little clear idea of how and why athletic nudity emerged as such a central part of their culture. Thucydides and Plato attribute the invention of athletic nudity to the Spartans and the Cretans, respectively, and indicate that (from their point of view) it set the Greeks apart from non-Greeks as especially civilised. However, it is not clear from their discussions how, when or why this state of affairs might have arisen. The cultural convention of athletic nudity probably originated so far back in time from the point of view of these authors that they had no direct knowledge of its advent.

Archaeological and iconographic evidence is more helpful. The earliest coherent collection of images of nude males in the Aegean take the form of diminutive bronze figurines. They appear in ritual deposits from just a few sites on the island of Crete and in the southern Greek region of the Peloponnese. The largest collection comes from the site of Olympia, where, as far as we can tell, supra-regional athletic contests (the ultimate progenitors of our modern Olympic games, of course) first arose as a prominent part of Greek culture.

Statuette of an athlete, bronze (510-500 BCE). Courtesy the Cleveland Museum of Art

Later textual and documentary evidence plausibly identifies these sites as rural religious sanctuaries that hosted initiatory rituals for young members of the community undergoing a transition from childhood to adulthood. Initiatory ceremonies (sometimes called liminal rites) are a common feature of human societies, and have thus been studied extensively by anthropologists. They generally involve a special costume, which often takes the form of complete nudity. Such costumes help community members recognise the special status of the initiate and the extraordinary context of the ritual as a moment outside the normal boundaries of social life. Most likely (as I have explored in my recent book on the topic), Greek nude athletic contests originated in liminal ceremonies that required young community members to visit rural sanctuaries and engage in nude physical contests to effect a socially mediated transition from childhood to adulthood.

This development is of interest, but it is not particularly helpful in explaining the central role that the naked male would eventually possess in Greek art and society. Many societies, including our own, incorporate initiatory rites that involve nudity (though today these are often shaded from view in dank fraternity basements during secretive induction ceremonies, etc). The real question, then, is why and how nude contests in ancient Greece went from an obscure, secretive and evidently not-very-common ritual practice to a defining feature of Greek society.

Working out naked generated an exclusive and visible form of hard-earned street credibility: the perfect suntan

Of the scenarios that have been put forward, the most convincing arises from nuanced sociological arguments made by the historian Paul Christesen in his book Sport and Democracy in the Ancient and Modern Worlds (2012). His arguments return us to a previous point about the central role that Greek athletics seemed to play in reifying the elite, male, citizen population within communities. Greek city-states like Athens and Sparta relied, to some extent, on the cohesiveness of their male citizen cohorts, who constituted core political and military bodies. Without the proper functioning of these cohorts, the states would have faced serious existential problems.

According to Christesen’s model, the practice of regular nude exercise together in the gym enhanced group coherence among these men, extending bonds cemented in youth initiatory contexts forward throughout the lives of adult citizens. Crucially, the practice of working out totally naked also generated a powerfully exclusive and highly visible form of hard-earned street credibility: the perfect suntan. If only citizen males of a certain socioeconomic class were regularly permitted and encouraged to work out naked, it follows that this group would likewise sport an otherwise difficult to achieve and distinctive tan unavailable to the farmer who spent long days doing menial labour under the hot sun wearing clothing conducive to safety and comfort. An interesting glimpse into the sociology of the tanned body in Greek gym culture is provided by some relevant vocabulary words – the adjective melampygos (‘dark-rumped’) is used to describe privileged citizens, while leukopygos (‘white-rumped’) connotes weakness, a lack of manhood, and cowardice.

According to this sociological model, the ideal of the nude male as model citizen and artistic paragon arose from a situation in which the best people in the community were visually marked specifically because of what they looked like naked. Christesen’s model is powerfully logical, but it still doesn’t explain everything. Returning to the Foundry Cup, the equipment hanging above the two large, clothed figures who frame and observe workers finishing the warrior statue includes little bottles (aryballoi) of oil and strigils, or tools athletes used to scrape oil, mud and sweat from their bodies following a workout. These visual clues tell us that the figures are passing by the foundry on their way to the gymnasium. If nudity is primarily a marker of status, then, it is perplexing to see that the Foundry Painter chose to depict the metalworkers in various states of undress, while the citizen-athletes are clothed. What could be going on here? Could the vase painter be making some kind of claim to citizen status for the craftspeople, a group of which the painter would also have been a part? Or was the inversion supposed to be funny, a visual joke to be consumed by drunk, upper-class participants in a symposium (a fancy drinking party)? Scholars remain at a loss to explain such conundrums, and it is unlikely that sure answers will emerge, given the complexity and sophistication of Greek visual culture. Still, it is valid to assert that class distinctions and nudity were tightly intertwined in ancient society.

Another factor that probably played a major role in centring the nude young male in Greek life and art is often underplayed in historical discourse, because it causes a certain amount of discomfiture for our modern sensibilities. The Greek gymnasium was a sexually charged place where erotic relationships were strongly encouraged, because such relationships were part of the educational system. Thomas Scanlon’s work, such as his book Eros and Greek Athletics (2002), has emphasised the longstanding relationship between Greek nude sport and pederasty, arguing that regular nude athletic practice served primarily as a venue for the formation of erotic relationships between mature men and adolescents, wherein the mature men leveraged erotic attachment to successfully acculturate young people according to certain expectations and norms.

Although the nuances and details of the emergence of these cultural institutions elude us, evidence from a site called Kato Syme in the mountains of south-central Crete supports a scenario in which homoerotic bonding was characteristic of nude athletic contests from an early date. For example, a bronze figurine dated to the 8th century BCE shows two males, one larger than the other, holding hands, and evidently in an apparent state of sexual arousal. This figurine resonates with a description by the (much later) author Strabo, who links eroticism, pederasty and coming-of-age rituals in very explicit terms when describing the institutions of Cretan society. This evidence indicates that nude athletics as specifically practised among Greek citizen males probably always played a powerful role in facilitating a particular system of socialisation that relied on the development of close, homoerotic bonds that tied together older and younger members of the male community in mutually beneficial pedagogical relationships.

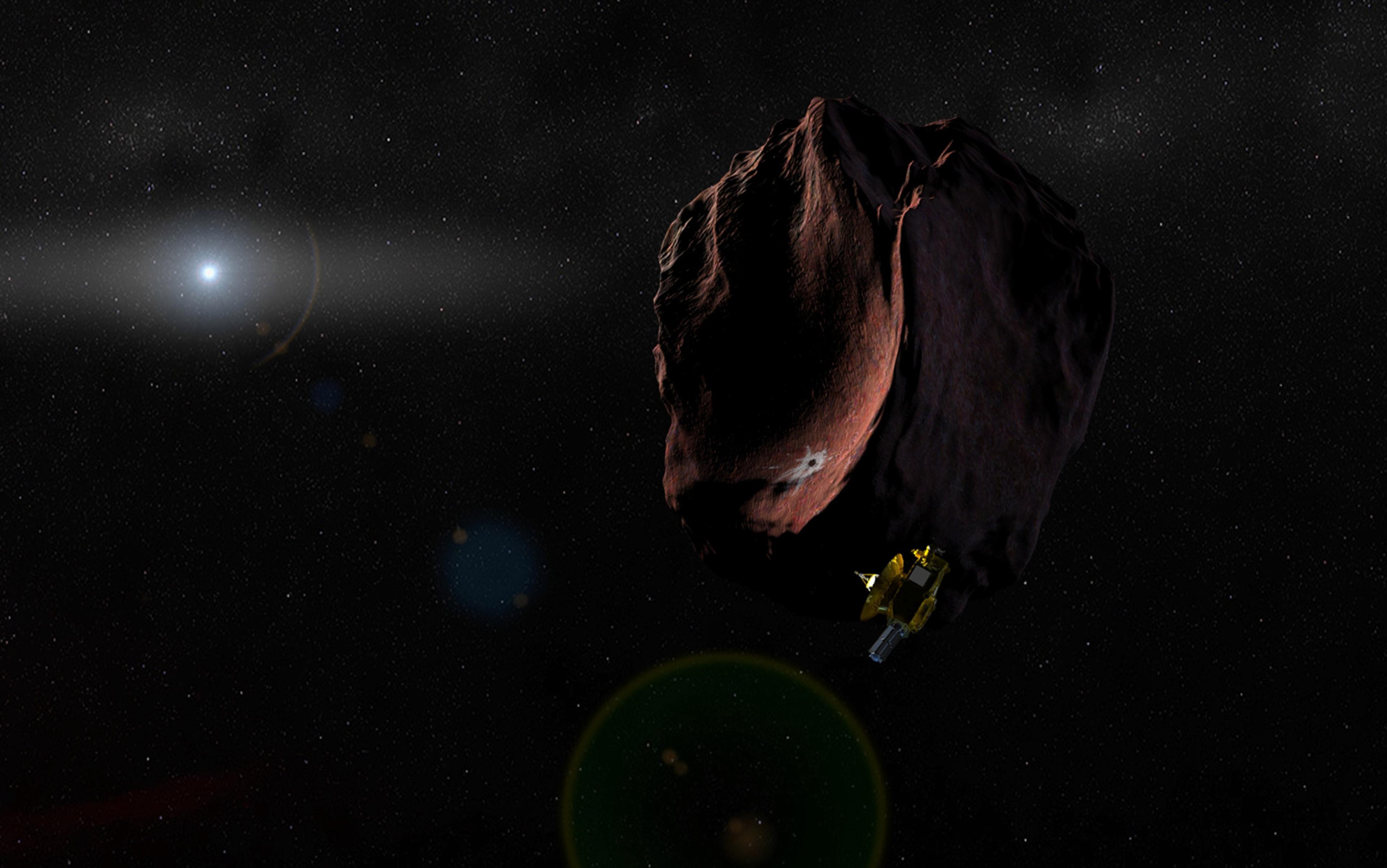

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora, attributed to the Euphiletos Painter (c530 BCE). Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

It is difficult to be certain how initiatory nudity, athletic nudity and civic nudity all came together into a cultural nexus during the long development of these institutions throughout the early 1st millennium BCE. Likewise, the exact relationship between a culture of socioeconomically circumscribed, single-sex, nude sport and the broader mechanisms of institutionalised homosexuality is difficult to reconstruct. Probably these matters all varied regionally within the complex Greek world, and evolved over time. To some extent, much of the ancient world will remain mysterious to us because our source material is fragmented and often not particularly forthcoming about the questions we would most like to answer.

What we can say, however, is that a deep dive into the history of the naked male in Western art reveals that the origins of this particular aesthetic type have little to do with what we tend to imagine as core tenets of Greece’s cultural legacy in 21st-century society: democracy, rule of law, philosophical enquiry into the fundamental characteristics of beauty and truth, and so forth. Quite the contrary, given what we do know and what we can reconstruct about such matters, the relict tendency towards male nudity in art that follows a classical tradition finds its origins in aspects of Greek culture that we find a bit unsavoury to contemplate.

Ultimately, the Greek ideal of a naked male arose from the exclusionary nature of Greek athletics: only a select group of relatively wealthy males could compete, and so the nude athletic male body became a powerfully normative image that reified the superiority of the culturally dominant sociopolitical group. Moreover, the Greek ideal of beauty was a young naked boy on the cusp of puberty, because older Greek males were encouraged to seek out such young boys as lovers, so that they could in turn educate the boys about virtuous values and proper ideas. This was a fundamental part of the Greek educational system, and was seen as a crucial form of socialisation that produced ideal citizens. It is difficult to deny the elegance of a simple explanation for the prevalence of nude dudes in Greek art: they were the ultimate, high-class sex symbol and – then as now – sex always sells.