… the Marranos, with whom I have always secretly identified (but don’t tell anyone) …

– from ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’ (1994) by Jacques Derrida

What is it to have a secret? What does it reveal about who we are?

We are used to regarding secrets as duplicitous. By hiding the truth, we are attempting to fool someone. Sometimes, the ends we are hoping to achieve may be beneficial, such as the little white lies we tell our friends or the case of various resistance movements, whose members are ‘sworn to secrecy’. But, in general, we are used to viewing secrets with distaste, associating them with lies. In having a secret, in keeping a secret, we must present to the world a false face. When challenged, we must say something that is not true. To have a secret is also a form of betrayal – I know something you don’t know, and I am denying you that knowledge deliberately.

To some, it is the deliberate nature of keeping our knowledge from another – be it an individual, a group, a society – that perhaps defines what a secret is. One cannot, it is generally felt, have a secret one does not know one has. One must, in some sense, deliberately and consciously decide not to tell. Thus, a secret is something that I do not put into words, but which I tell myself. One does not carry a secret inside unless one has performed this act, until one has enunciated to oneself what it is one wishes to keep secret, and made the decision to let no one else hear the words one has spoken to oneself.

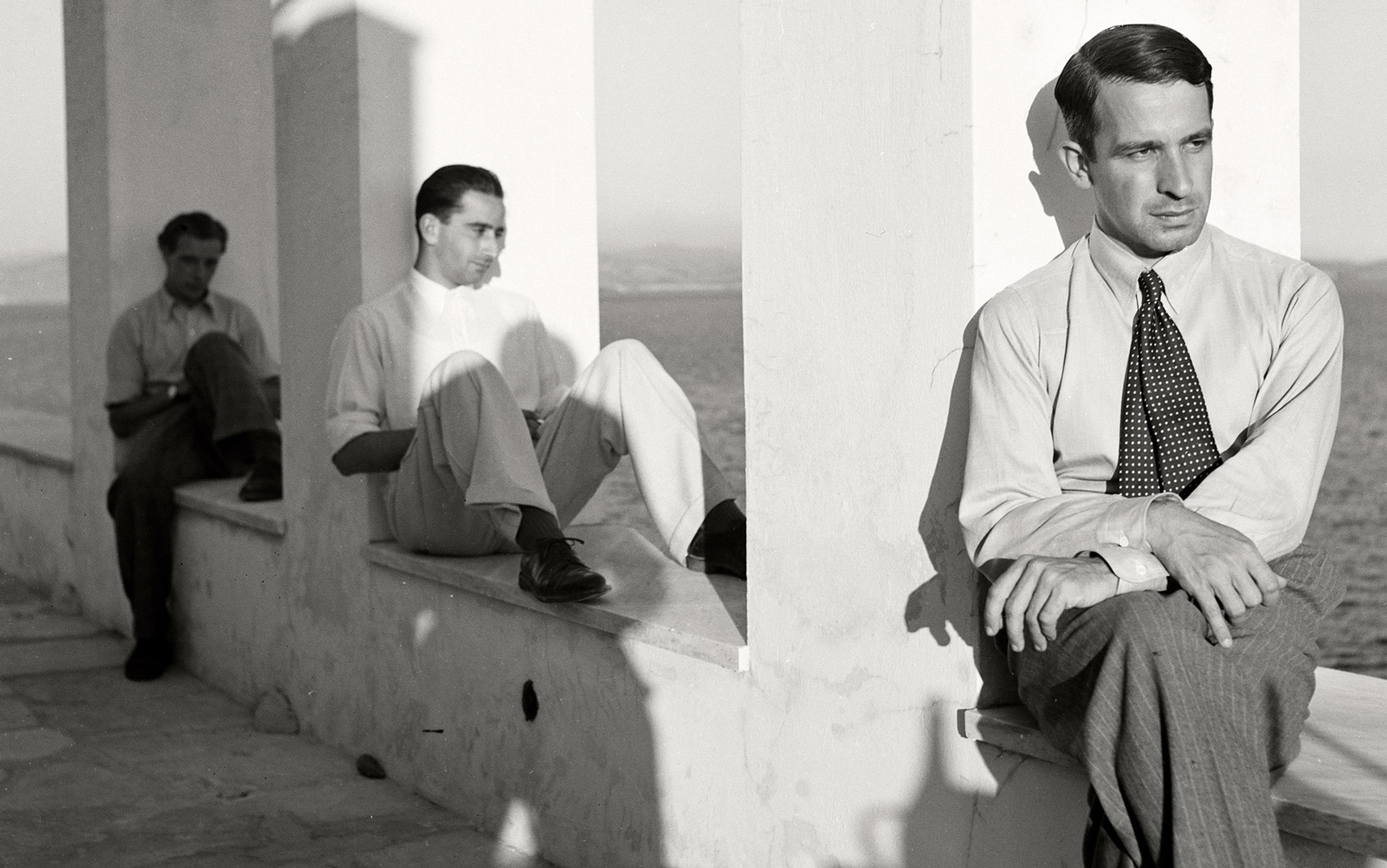

For the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, best known for his idea of deconstruction, the idea of secrets exerted a huge fascination. Like all philosophers, he was always hugely interested in what we might roughly call ‘consciousness’, the part of our thinking of which we are aware, and to which we feel most intimately connected. This is the part of our thinking we tend to regard as ‘us’ – we have our opinions, our preferences, our thoughts about this and that. This idea has been central to Western philosophy. René Descartes, for instance, argued that knowing we are conscious was all we could be sure of – I think therefore I am – while Jean-Paul Sartre argued that it is both the source and the guarantor of our freedom.

In the late 19th and throughout the 20th century, a number of philosophers, Derrida among them, have performed a radical critique of this position. The idea that we have some sort of pure access to consciousness, and indeed that consciousness is some sort of pure expression of our selfhood is, they argue, highly questionable, if not downright false. Consciousness is as constructed as our ability to count – it is learnt. The fact that we communicate with ourselves – that voice in our head – in the language we have learned from the society in which we live is a banal example of this. In another time or place, I would ‘think’ differently about everything. There is, the argument goes, no basic, pure ‘me’ underneath all the ways of thinking I have learned. The voice in my head is not my own.

Derrida’s early work deconstructed the ways in which we mistake the ‘voice in our head’ for our ‘selves’. In religious thinking, we even mistake it for our ‘soul’. For Derrida, anything that has been ‘constructed’ can be ‘deconstructed’, a form of taking apart of something without destroying it. It is a method of seeing what factors have come together to make us understand something as a particular thing – be it ‘God’, ‘truth’, or ‘the self’.

In the case of the self, we take a huge number of disparate factors and then give them a unifying label, in my case ‘Peter Salmon’. This is what I call my ‘identity’ – it is the name I sign to an essay like this (also made up of disparate factors but made to appear whole), but also to legal documents, social media, and the name I give to introduce myself. My book about Derrida, An Event, Perhaps (2020), has my name on the front, I declare it to be my ideas.

But none of these identities is a full representation of myself – there is in each a degree of secrecy. Nowadays, for instance in social media, we are very aware that we keep secrets: one doesn’t usually want one’s boss to know about one’s parties or relationships, while there are undoubtedly things we will not tell either our parents or, in some cases, the taxman.

Questions of identity and secrecy were always present for Derrida, from his early work in the 1960s to his late work at the turn of the 21st century. This was due in part to an extraordinary moment in his own life. Born in Algeria, a French colony, in 1930, he was a schoolchild when the German occupation of France saw Algeria introduce new anti-Jewish legislation. Derrida was sent to a Jewish school with other Jewish students and teachers, and lost his French citizenship. For the young Derrida, this was not just a personal calamity – although it was certainly that. He came to understand how arbitrary and fragile our sense of identity can be, and how it can be taken from us by outside forces – and that, sometimes, we must keep secrets to survive. Derrida’s family were secular Jews, and suddenly ‘being Jewish’ was the main thing about him as far as the law was concerned, and the law at that point was everything.

A year later, the war conditions changed, and his French citizenship was restored. The 13-year-old Derrida found this no less baffling and traumatic. Suddenly, his identity was changed again (although not in the fullest sense ‘restored’ – one could not be what one was before, especially after trauma).

Doesn’t a secret imply others – more than imply, does it actually depend upon them?

Derrida’s genius was to understand that, while his own instance was dramatic, this fragility and arbitrariness of identity is a condition all humans in some sense share. I am a different person writing this to who I am spending time with friends, making love, or visiting the doctor. I am also a different person in the eyes of the law (or laws), and my status can change as laws change. Or in a war. Or if I emigrate. Or if I seek refuge (and Derrida was particularly interested in this; if I seek refuge, I am a ‘refugee’: ‘I was a doctor in Ukraine, I am now a cleaner in London’).

What then, of ‘the secret’? If a secret really is something I tell only myself, is there something here that is mine and mine alone, that survives as my true ‘self’, more basic than the many roles I play out socially? But, he asks, without other people, could I have any secrets? Doesn’t a secret imply others – more than imply, does it actually depend upon them?

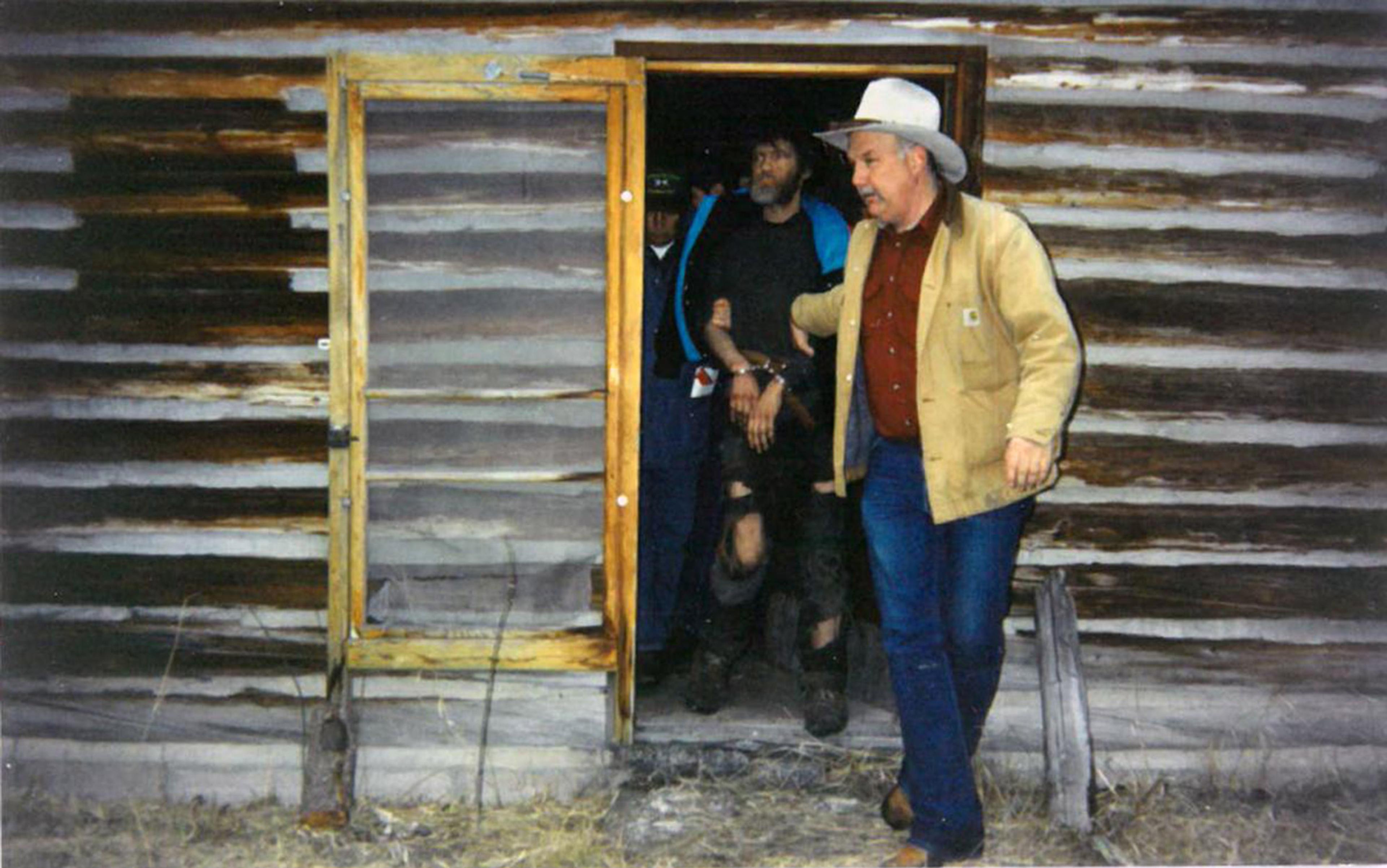

Derrida’s response to this idea is a complicated one (as Derrida’s relationship to any idea tends to be). What fascinates him is the place of secrecy in our lives, our discourse and our relationships. There is, he argues, a secret history of secrets. This secret history is, among other things, a political history. Derrida notes that one might define a totalitarian state as one in which no one is allowed secrets. George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1948) is an exemplary telling of this. Winston Smith’s secret is his love for Julia, he is forced to yield up this secret, and having done so now loves ‘Big Brother’. But we see it in any number of police states – to have a secret is to be a traitor, and the point of a trial is not simply to punish, but to make evident the state’s power over every aspect of the individual. You will have no secrets.

These are extreme examples but this situation is not exclusive to totalitarian regimes. In democratic societies, there are particular flashpoints around attempts to gain, or defend, personal information, and around what the state is able to do in order to access our secrets. To be tried by the state is to forfeit the right to various aspects of one’s personal privacy, up to and including secrets. In fact, many of our legal protections are based on the assumption that we cannot access the secrets of another – one often has to prove criminal intent or mens rea to convict, and intent is an opaque concept indeed.

For Derrida, the idea of the secret is intimately bound up with the idea of ‘confession’, be it political, personal or religious. Confession need not be forced, of course. In fact, it can be an act of love. If I confess to you my ‘deepest secrets’, I am – in commonsense belief – ‘telling you who I really am’, or rather showing you who I really am, by performing a kind of revelation that makes me vulnerable and open, and inviting a reciprocal openness. I trust/love you so much that I have no secrets. More prosaically, it can also be an act of profound friendship – another of Derrida’s themes – and of bonding. When someone says: ‘Do you want to know a secret?’ we feel not only the thrill of the illicit, but a sense of being entered into a community, even if it is one of only two people. We share secrets.

In each of these examples, confessions forced or otherwise, the tacit understanding is that the confession is indeed an act of revealing the self. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston exposes his secret and destroys his ‘self’. If I confess to you my secrets, you enter into my most intimate selfhood, we share it. Thus, we have a commonsense – and legalistic – belief that there is a direct relationship between our secrets and our selves. This is also, traditionally, a religious belief, and the connection between religion and secrets is a powerful and enduring one. The Catholic rite of confession is an exemplary model of this. To the priest, I reveal my secrets, and therefore my true self, the self only God otherwise has access to. If I keep secrets from the confessional, the self I offer up to God and the self that God knows to be true are misaligned. I betray God because I withhold information from His representative/proxy on Earth. Thus, Catholic guilt – the guilt of non-confession, the guilt of the unmentioned transgressions in both thought and act.

For Derrida, as the philosopher Agata Bielik-Robson points out in her excellent book Derrida’s Marrano Passover (2022), it was his interest in one particular religious group that opened up his own dialogue with the idea of secrets – a group so secret that it forgot that it disguised its own existence even to itself.

On 4 June 1391, a massacre of Jews took place in Spain and Portugal. A rampaging mob burned down houses in Seville, attacked places of worship, and killed around 4,000 Jews. The mob sacked the Jewish enclave, in what was the first stirring of a religious fanaticism that, a century later, would usher in the Inquisition. The attacks spread throughout the Spanish Peninsula – Córdoba, Valencia, Barcelona. Even on the Balearic Islands and in Granada, the entire Jewish population disappeared.

But not every missing Jew had been killed. Many had been baptised, usually by force, into the Catholic faith. These ‘New Christians’ came to carry a number of names – they were conversos, anusim (meaning ‘forced ones’) or crypto-Jews. But they are best known by a name translated as ‘dirty pigs’ (that this name pointed to the Jewish refusal to eat pork is no coincidence): the Marranos. What is in some ways unique about the Marranos, and what fascinated Derrida, was their persistence. They used complex ruses to hide their continuing but concealed Jewish faith, such as finding ways to not work on the Sabbath – one popular method was to place a child behind their shop counters who could claim to investigators that their parents had just stepped out – and to adopt Catholic rites that could be squared with their Jewish faith, such as avoiding lessons and rituals that proclaimed the divinity of Christ.

The one word of Hebrew they knew was Adonai, the Hebrew word for God

Over the past 600 years, these ruses not only protected the Marranos from persecution. They also created a new religion, unmoored in many ways from both its original sources. Due to its secrecy, it became a fusion of overt Christian and covert Jewish practices, and yet is disconnected from both. Much traditional Jewish ritual is lost to the Marranos. There are – uniquely for these ‘People of the Book’ – no texts, and Christian rites are transmuted into hybrid Jewish ones (and vice versa).

Extraordinarily, for the Marranos, Hebrew is an unknown tongue, except for one word. In 1990, when the filmmaker Sam Neuman documented a small community of Marranos in the village of Belmonte, Portugal, the one word of Hebrew they knew was Adonai, the Hebrew word for God. But of course, this not the true name of God in the Jewish tradition.

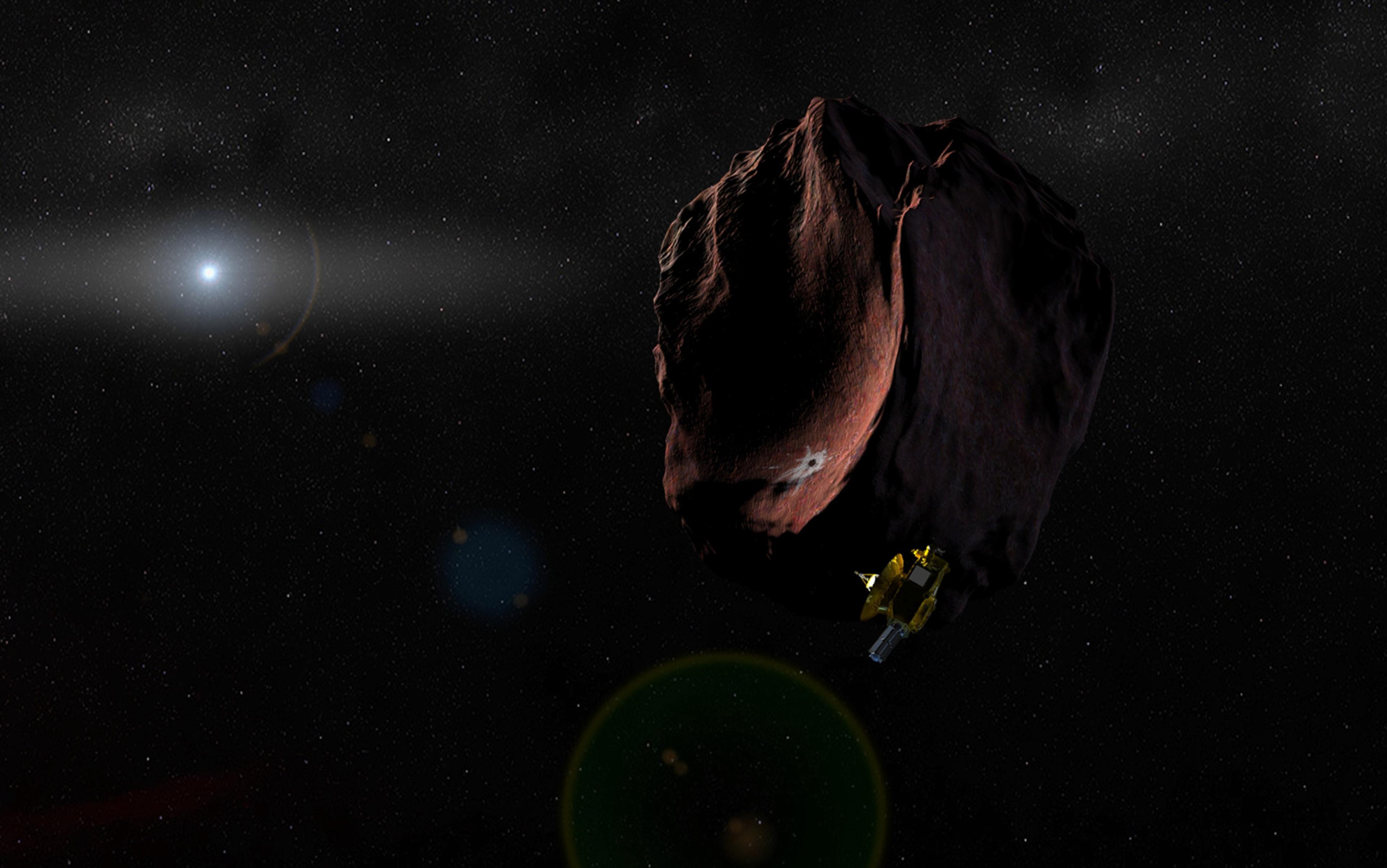

The true name of God is a secret.

Derrida’s fascination with the Marranos came late in his thinking. In a 1999 documentary about his life, speaking in a Catholic church in Toledo – a building that was once a synagogue, then a mosque, before becoming a Christian church – he says:

What is an absolute secret? I was obsessed with this question quite as much as that of my supposed Judeo-Spanish origins. These obsessions met in the figure of the Marrano.

Derrida was drawn to marranism, as he came to call it, for a number of reasons, including this tension between an individual having no essential ‘I’, and the persistence of the idea of the secret as exemplary in revealing an ‘I’ that is the true self. But marranism, for Derrida, is also an example of ‘religion without religion’ – simply to declare one’s faith, to confess it, is to lose it. Or, at times, even to lose one’s life. The Marrano experience is, therefore, an extreme example of what many Jews of the 20th century experienced when, as Hannah Arendt pointed out in her essay ‘The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition’ (1944), one had to conceal one’s identity, in this case Jewish, to be allowed to speak and even to live. It is a condition not exclusive to Judaism but, at the time of Arendt’s writing, it had a particular significance.

Thus, as the Latin-American scholar Alberto Moreiras has argued in Against Abstraction (2020), ‘marrano is not something one is but rather something that happens to one’ – such as being a 13-year-old French citizen one moment, and a 13-year-old Algerian Jew the next. Had Derrida’s family been living in France, they may well have been among the 72,500 French Jews exterminated by the Nazis. Or they could, perhaps, have tried to keep their Judaism secret, become crypto-Marranos.

For Derrida, we can always keep digging into the crypt of our self, and we’ll never uncover the body

But for Derrida, the Marrano experience goes beyond the moment of conversion (and/or betrayal), and even beyond the following generations who in some sense kept the menorah candle burning. ‘I am,’ writes Derrida, ‘one of those marranos who no longer say they are Jews even in the secret of their own hearts.’ Instead of a secret we are conscious of, here is a secret that is unconscious. ‘It is perhaps there that we find the secret of secrecy,’ Derrida writes.

Here Derrida’s thinking touches – as it often does – on psychoanalysis. The task of the psychoanalyst is to draw from the one being analysed not only the secrets of which they are aware – here the psychoanalyst acts as both lover and priest – but those that have been repressed. According to Sigmund Freud (himself later forced to flee potential extermination), our deepest secrets are those we cannot usually access ourselves. If common sense posits that the secrets we deliberately keep may be closest to our true selves, so psychoanalysis argues that it is in fact the secrets that are secrets from ourselves, the ones we suppress, that are the truest, affecting our behaviour in large ways and small. And as the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has pointed out, these secrets are often hidden in plain sight, like the ‘purloined letter’ in Edgar Allen Poe’s short story of that name, but are no less hidden for that.

For psychoanalysis, the cure is, again, putting those secrets into words. There is nothing blasé about this in analysis – for some, this level of confession is as torturous as an inquisition, and the self is put at risk by the process. And no resolution is guaranteed – one secret leads to another and is as ‘interminable’ as Jewish theology – every question is answered by another question. This for Derrida is one of the important secrets of secrets – there is not some final secret that defines us, that gives us our identity and unlocks who we truly are. Here his approach differs from that of Freudian theory if not practice – for Derrida, we can always keep digging into the crypt of our self, and we’ll never uncover the body.

To avoid the trap of confession, one can only choose silence. But as the philosopher Gerhard Scholem, himself a chronicler of the Marrano experience, wittily put it in 1918: ‘The person able to be silent in Hebrew … there is no one among us who can do this.’ Least of all Derrida, who writes:

I would not want to let myself be imprisoned in a culture of the secret, which however I do rather like, as I like that figure of the Marrano, which keeps popping up in all my texts.

As Bielik-Robson notes: ‘Derrida never emphasises his Jewishness but also never silences it either.’

The final and unavoidable silence is, of course, death. In this act, we take our secrets to the grave. Derrida was no exception – in his final interview, a few weeks before he died in October 2004, this great literary confessor said:

When I recall my life, I tend to think that I have had the good fortune to love even the unhappy moments of my life, and to bless them. Almost all of them, with just one exception…

What this exception was, though, Derrida kept secret.