Several years ago, Arla, one of the largest dairy companies in the world, set out to create a product to take advantage of an inviting opportunity. Consumers were increasingly seeking out protein as a healthful nutrient, and whey protein, derived from milk, was seen as the most desirable kind, especially by athletes. Isolating protein from whey and adding it to clear drinks could make them more appealing to consumers and make Arla a lot of money, but there was a problem: the flavour. Whey protein has a milky taste and, separated from milk’s natural fat and sugar, it has a dry mouthfeel. It didn’t take a marketing genius to predict the demand for water that tasted like dry milk.

So ‘dairy technicians’ at Arla Food Ingredients set out to create a better whey protein. After years of development, the company recently released eight kinds of whey protein isolate that dissolve in water and become practically undetectable to the senses: essentially no taste, smell, cloudiness or dry mouthfeel. The protein isolates are food ghosts, an essence of nutrition utterly devoid of substance.

Arla Food Ingredients sells the protein isolates to companies that add them to consumer products. All eight have the same general properties, with each individually tuned for different applications. Lacprodan SP-9213, for instance, remains stable under acidic conditions. Imagine a glass of orange juice with the protein of an omelette.

Arla is secretive about how much it sells or what specific products it’s used for, saying only that its isolates are used by some of the biggest food companies in the world. But the Danish multinational gives strong hints about one application: ‘Tea, which has been the drink of choice for millions of people around the world for centuries, has a powerful association with wellness. Meanwhile, protein’s benefits in areas such as weight loss and muscle growth are increasingly sought after by consumers,’ says a product manager at Arla. ‘Marrying these two trends to create the unique concept of high-protein iced tea makes complete sense.’

Adding ghostly milk protein to iced tea does make sense – according to certain views of what makes food healthful. Those views are as culturally dependent as the seasonings we place on our dining tables and as personally subjective as our preferences for ice-cream flavours.

The history of humanity is in no small part the story of our increasing control over our sustenance. Around 2 million years ago, our early human ancestors began processing food by slicing meat, pounding tubers, and possibly by cooking. This allowed us to have smaller teeth and jaw muscles, making room for a bigger brain and providing more energy for its increasing demand. Around 10,000 years ago, humans began selectively breeding plants and animals to suit our preferences, and the increased food production helped us build bigger and more complex societies. The industrial revolution brought major advancements in food preservation, from canning to pasteurisation, helping to feed booming cities with food from afar. In the 20th century, we used chemistry to change the flavour of food and prevent it from spoiling, while modern breeding and genetic engineering sped up the artificial selection we began thousands of years ago. The advent of humans, civilisation and industrialisation were all closely tied to changes in food processing.

Arla’s whey protein isolate is part of the latest phase of an important ongoing trend: after modern production drove the cost of food way down, our attention shifted from eating enough to eating the right things. During that time, nutrition science has provided the directions that we’ve followed toward more healthful eating. But as our food increasingly becomes a creation of humans rather than nature, even many scientists suspect that our analytical study of nutrition is missing something important about what makes food healthful. Food, that inanimate object with which we are most intimately connected, is challenging not only what we think about human health but how we use science to go about understanding the world.

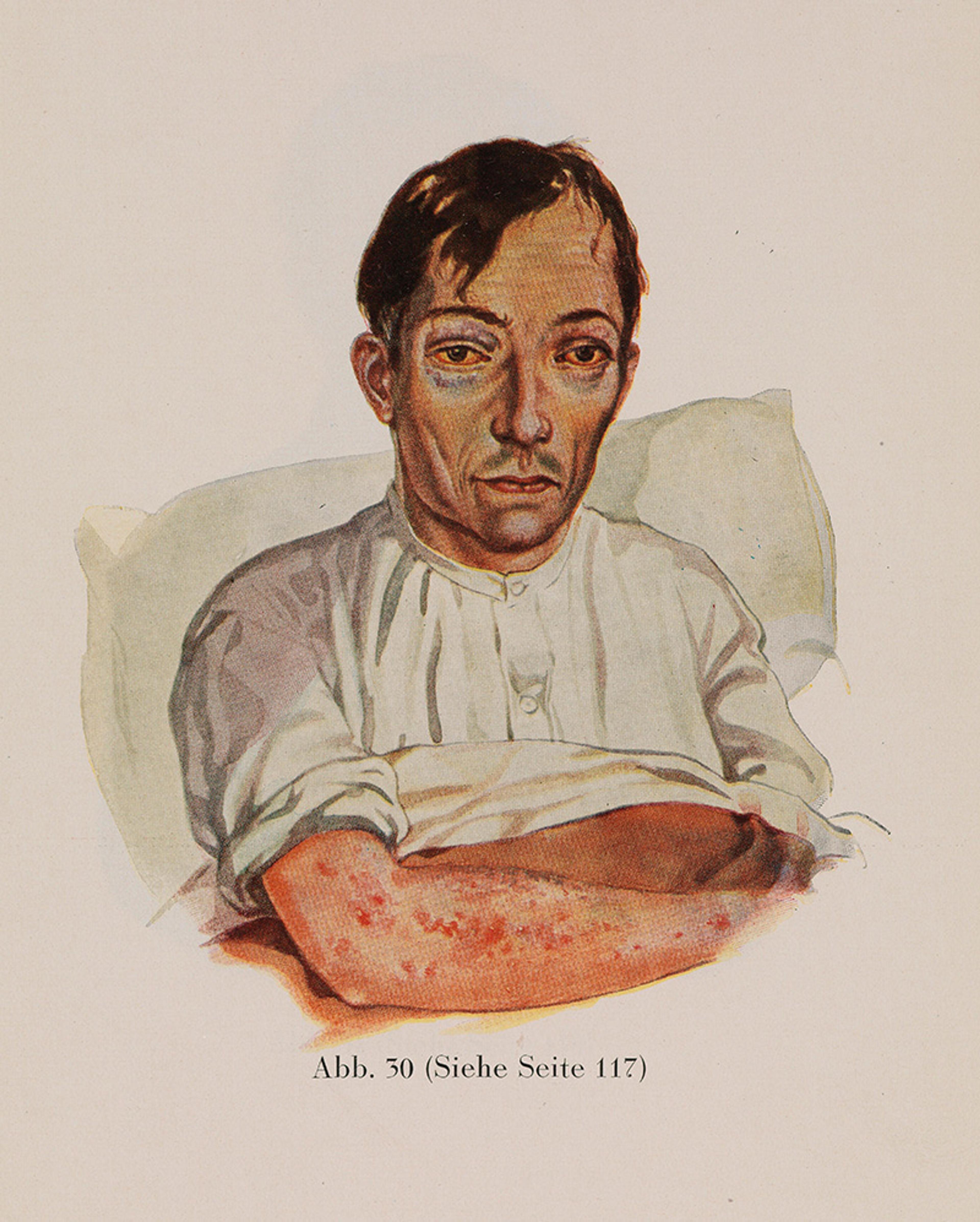

Nutrition science began with the chemical description of proteins, fats and carbohydrates in the 19th century. The field didn’t seem to hold much medical import; the research was mostly aimed at cheaply feeding poor and institutionalised people well enough to keep them from rioting. Germ theory, on the other hand, was new and revolutionary medical science, and microbiologists such as Louis Pasteur were demonstrating that one disease after another, from cholera to malaria to leprosy, was caused by microbes. But at the turn of the 20th century, nutrition science suddenly arrived as a major part of our understanding of human health.

The story of how humans were rid of scurvy now seems inevitable, even obvious: in the age of sail, men on ships ate preserved food for months and often contracted the disease; finally, they realised that eating citrus fruits could prevent scurvy, and that’s why Brits are called limeys and why we need Vitamin C, kids. That potted history leaves out the true costs of the disease and the tragically erratic way it was brought to an end.

Scurvy is a serious condition that causes weakness, severe joint pain, loose teeth, and can eventually burst major arteries, causing sudden death mid-sentence. On many long sail voyages, more than half of the people on board succumbed to the disease. Yet methods for curing or preventing scurvy had already been discovered many times by many peoples, from Iroquois Native Americans who boiled the leaves and bark of the eastern white cedar in water, to ancient Chinese who ate ginger on long sea trips. At the end of the 15th century, Vasco da Gama, the leader of the first European sea voyage to reach India, prevented scurvy in his crew by supplying them with citrus fruits. In 1795, the British navy mandated that every sailor at sea for long be given a ration of lime juice.

Again and again during this period, various people discovered that eating certain fresh fruits and vegetables reliably prevented the disease. But as many times as the solution was discovered, it was again forgotten or shoved aside for a different explanation. Part of the problem was what we would today call confounding variables. For instance, lime juice taken on ships to prevent scurvy was sometimes boiled, exposed to light and air for long periods, or pumped through copper pipes, which could degrade so much Vitamin C that it had little benefit. Some kinds of fresh meat also provided enough Vitamin C to prevent the disease, complicating the message that there was something special about fresh fruits and vegetables.

It’s likely the explorers unintentionally relieved the deficiency when they started eating fresh seal meat

Well into the 20th century, many doctors and scientists still had mixed-up understandings of scurvy. One theory common at the time, encouraged by the success of germ theory, held that it was caused by consuming ptomaine, a toxin produced by bacteria in decaying flesh, particularly in tinned meat. Before his expedition to the Antarctic in 1902, the English explorer Robert Falcon Scott employed doctors to search for the subtlest signs of rot in all the food brought aboard the expedition’s ships, especially the tinned meats. For a time, their measures seemed to work. ‘We seemed to have taken every precaution that the experience of others could suggest, and when the end of our long winter found everyone in apparently good health and high spirits, we naturally congratulated ourselves on the efficacy of our measures,’ Scott wrote in his memoir of the voyage.

But after the winter, many of the men did come down with scurvy, after which the disease mysteriously receded. Scott analysed the potential source of the problem at some length, eventually concluding that the problem was probably the tinned meat or dried mutton they brought on board from Australia, though he was stumped at how any dodgy meat slipped through their careful inspection. ‘We are still unconscious of any element in our surroundings which might have fostered the disease, or of the neglect of any precaution which modern medical science suggests for its prevention,’ he wrote. In retrospect, it’s likely that the explorers unintentionally relieved the deficiency when they started eating fresh seal meat from animals they caught.

Chemists would soon put their finger on the answer to the mystery. In 1897, Christiaan Eijkman, a Dutch researcher who had studied beriberi on Java, in Indonesia, noticed that when the feed of his experimental chickens had been switched from unpolished brown rice to polished white rice, the chickens began to show symptoms of a neurological condition similar to beriberi; and when their feed was switched back to the unpolished brown rice, the chickens got better. In 1911, the Polish chemist Casimir Funk announced that he’d isolated the beriberi-preventing chemical, which he thought to be a molecule containing an amine group, and named it ‘vitamine’ – a vital amine. The next year, Funk published an ambitious paper and book arguing that not only beriberi but three other human diseases – scurvy, pellagra and rickets – were each caused by a lack of a particular vitamin. Within a few months, the English researcher Frederick Hopkins published the results of a series of experiments in which he fed animals diets based on pure proteins, carbohydrates and fats, after which they developed various ailments. He posited that the simplified diets lacked some ‘accessory food factors’ important for health. Those factors and many others were discovered over the next three decades, and researchers showed how these vitamins were critical to the function of practically every part of the body. Ten of those scientists, including Eijkman and Hopkins, won Nobel prizes. At the same time that physicists laid out the theories of general relativity and quantum mechanics, describing fundamental laws that governed the Universe on its smallest and largest scales, chemists discovered the laws that seemed to govern the science of nutrition.

This new understanding of food was soon tested on a grand scale, when, at the dawn of the Second World War, the governments of the US and the UK found that many of their people suffered from vitamin deficiencies. The British government started feeding their troops bread made with flour enriched with Vitamin B1, while the majority of the US flour industry switched to flour enriched with iron and B vitamins under government encouragement. Pellagra, caused by a lack of Vitamin B3, was previously widespread in the American South, killing an estimated 150,000 people in the first half of the 20th century; after the introduction of enriched wheat flour, it all but disappeared overnight.

The US government also embarked on a campaign to convince people that these newfangled nutrients were important. ‘The time has come when it is the patriotic duty of every American to eat enriched bread,’ wrote the US surgeon general in a widely read article in the magazine Better Homes and Gardens. In 1940, only 9 per cent of Americans reported knowing why vitamins were important; by the mid-50s, 98 per cent of the housewives in a US Department of Agriculture study said that industrially produced white bread made from enriched flour was highly nutritious. The public health success and promotion of enriched bread helped to establish nutrients as a necessary component of human health, with food as their delivery mechanism. Bananas for potassium, milk for calcium, carrots for Vitamin A and, of course, citrus for Vitamin C. The value of food could be computed by measuring its nutrients and reflected in a nutritional label on the side of a package.

Over the 2010s, this nutrient-based model was pushed near its logical endpoint. In 2012, three college grads working on a tech startup in San Francisco were fast running out of funding. One of them, a coder named Rob Rhinehart, had an epiphany: he could simply stop buying food. ‘You need amino acids and lipids, not milk itself,’ he thought. ‘You need carbohydrates, not bread.’ Rhinehart did some research and came up with a list of 35 essential nutrients – a successor to the lists of vitamins that Funk and Hopkins had composed exactly 100 years before – and bought bags of them online. He mixed the powders with water, began consuming that instead of conventional food, and was beyond pleased at the result. ‘Not having to worry about food is fantastic,’ he wrote in a blog post. ‘Power and water bills are lower. I save hours a day and hundreds of dollars a month. I feel liberated from a crushing amount of repetitive drudgery.’ He and his roommates soon started a company to sell the powder, which they named Soylent to evoke the movie Soylent Green (1973), in which food was infamously made from humans. (Reinhart’s mix was mostly soya, as in the 1966 sci-fi novel the film was based on, Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, where ‘soylent’ is a mix of soya and lentils.)

Around the same time, the Englishman Julian Hearn was starting his second business, a company called Bodyhack. Hearn had recently changed his diet and decreased his body-fat level from 21 to 11 per cent, and he wanted to market similar interventions to other people. But while weighing ingredients for recipes, he realised it would be more convenient if preparing meals was as simple as blending up his daily protein shakes. As much as we like to think of eating as a time for communal partaking of nature’s bounty, Hearn says most meals are affairs of convenience – breakfasts grabbed in a rush before work, dinners picked up on the way home – and that a quick, nutritious smoothie is far better for people and the planet than the junky fast food that we often rely on. Hearn soon pivoted from Bodyhack and launched a company to sell powdered food that was convenient, healthful, and Earth- and animal-friendly. He named it Huel, pushing the idea that food’s main role is human fuel. ‘It’s quite bizarre that as a society we prioritise taste and texture,’ Hearn says. ‘We can live our whole lives without taste.’ He recommends that Huel customers continue to enjoy some sociable meals of ‘entertainment food’ – ‘I’d never be able to give up my Sunday roast,’ he says – but that ‘in an ideal world, I think everybody should have one or two meals a day of food that has a long shelf life, that is vegan, with less carbon emissions and less wastage.’

Foodies howled at engineering’s tasteless encroachment on one of their great joys

Meal-replacement mixtures have been around for decades, but the new companies put more care into making ‘nutritionally complete’ products with higher-quality ingredients. They also tapped into cultural forces that their predecessors had not: the rise of tech culture and lifehacking. The founders of Soylent, already dialled in with the startup scene, pitched their creation as a way for idea-rich but time-poor techies to get more done. It also jibed with the Silicon Valley obsession with efficiency and ‘disrupting’ old ways of doing things. Years before becoming a tech icon, Elon Musk captured this mindset when he told a friend: ‘If there was a way that I could not eat, so I could work more, I would not eat. I wish there was a way to get nutrients without sitting down for a meal.’ Soylent became popular with Musk wannabes in the Valley, and though the company’s growth has slowed, Huel and a wave of others have succeeded in bringing powdered meals to a growing crowd of busy, data-driven nutrition-seekers.

Foodies with no interest in disrupting their diets or replacing mealtime with work time howled at engineering’s tasteless encroachment on one of their great joys. Sceptical journalists hit their keyboards with unabashed glee. ‘Imagine a meal made of the milk left in the bottom of a bowl of cut-rate cereal, the liquid thickened with sweepings from the floor of a health food store, and you have some sense [of the new food powders],’ wrote the food editor Sam Sifton in The New York Times in 2015. ‘Some of them elevate Ensure, the liquid nutritional supplement used in hospitals and to force-feed prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, to the status of fine wine.’

The new powdered-food companies also came in for plenty of criticism from a group they might have expected to be on their side: nutritionists. When journalists covering the new trend came calling, many professional diet advisors pooh-poohed this new food trend. Why did they so adamantly oppose products that sprang directly from the published, peer-reviewed science that defines their own field?

In 1976, a group of researchers at Harvard University in Massachusetts and several affiliated hospitals launched a research project to pin down how various behavioural and environmental factors such as smoking and contraceptive use affect health conditions such as cancer and heart disease over the long term. They decided to enrol nurses, figuring that their dedication to medical science would help keep up their enthusiasm and participation. The landmark Nurses’ Health Study enrolled more than 120,000 married women in 11 populous states and helped show, for instance, that eating trans fats caused increased rates of heart disease and death.

But the study’s data turned out to be a mixed blessing. In one analysis of in 2007, researchers noted that women who ate only non-fat or low-fat dairy had less success getting pregnant than other women who ate some full-fat dairy. The researchers suggested that if women increased their consumption of fatty dairy products, such as ice-cream, that could increase their chances of conceiving. ‘They should consider changing low-fat dairy foods for high-fat dairy foods,’ said the head of the 2007 study, suggesting that women adjust their diet elsewhere to compensate for the ice-cream calories, apparently assuming that we all keep detailed records of how many calories we eat. ‘Once you are pregnant, you can always switch back.’ This observation was then translated to headlines proclaiming: ‘Tubs Of Ice Cream Help Women Make Babies’ (in the New Scientist magazine) and ‘Low-Fat Dairy Infertility Warning’ (on the BBC News site). ‘In fact, the researchers had little confidence in that finding, and they cautioned that ‘there is very limited data in humans to advise women one way or another in regards to the consumption of high-fat dairy foods.’

While the recommendation for eating ice-cream was a blip that soon disappeared down the river of news, other questionable nutrition findings have stuck around much longer, with greater stakes. In the latter half of the 20th century, nutritionists formed a rough consensus arguing for people to eat less fat, saturated fat and cholesterol. The missing fat was, mostly, replaced by carbohydrates, and rates of obesity and heart disease continued to climb ever higher. Many nutritionists now say that replacing fat with carbohydrates was an error with terrible consequences for human health, though some cling to modified versions of the old advice.

Many experts say the biggest problems in the field come from nutritional epidemiology, the methodology used in the Nurses’ Health Study and many others, where researchers compare how people’s diets correlate with their health outcomes. Nutritionists of course know the truism that ‘correlation does not imply causation’, and all of these studies try to account for the important differences in the groups they study. For instance, if a study compares two groups with different diets, and one of those groups includes more people who smoke or are overweight, researchers try to subtract out that discrepancy, leaving only the differences that stem from the groups’ varied diets. But human behaviour is complicated, and it is difficult, at best, to statistically account for all the differences between, say, people who choose to eat low-fat diets and those who choose to eat low-carbohydrate diets.

The US writer Christie Aschwanden demonstrated how easily nutritional epidemiology can go awry in a piece on the website FiveThirtyEight in 2016. She ran a survey of the site’s readers, asking them questions about their diets and a range of personal attributes, such as whether they were smokers or if they believed the movie Crash deserved to win a best-picture Oscar. One association she turned up was that people who are atheists tend to trim the fat from their meat. She interviewed the statistician Veronica Vieland, who told her it was ‘possible that there’s a real correlation between cutting the fat from meat and being an atheist, but that doesn’t mean that it’s a causal one. ’

There were very strong correlations between eating cabbage and having an innie belly button

Aschwanden concluded: ‘A preacher who advised parishioners to avoid trimming the fat from their meat, lest they lose their religion, might be ridiculed, yet nutrition epidemiologists often make recommendations based on similarly flimsy evidence.’ This is the problem with the finding that eating high-fat dairy can increase fertility, she argued. There might be a connection between women who eat ice-cream and those who become pregnant but, if so, it is likely that there are other ‘upstream’ factors that influence both fertility and dairy consumption. The conclusion that ice-cream can make you more likely to conceive is like the conclusion that eating leaner meat will make you lose your faith.

Studies that compare people’s diets with their health outcomes are also notoriously prone to finding associations that emerge purely by chance. If you ask enough questions among one set of people, the data will ‘reveal’ some coincidental associations that would likely not hold up in other studies asking the same questions. Among people who took Aschwanden’s survey, there were very strong correlations between eating cabbage and having an innie belly button; eating bananas and having higher scores on a reading test than a mathematics test; and eating table salt and having a positive relationship with one’s internet service provider. It seems unlikely that eating salty food makes you get along better with your ISP: that was just a random, unlikely result, like flipping a coin 13 times and getting 13 heads. But the association was significant according to the common rules of scientific publishing, and many critics of nutritional epidemiology say the literature is chock-full of this kind of meaningless coincidence.

Critics say these two weaknesses of nutritional epidemiology, among others, have caused widespread dysfunction in nutrition science and the notorious flip-flopping we often see playing out in the news. Do eggs increase the risk of heart disease? Does coffee prevent dementia? Does red wine prevent cancer? There is not even a consensus on basic questions about proteins, fats and carbohydrates, the basic categories of nutrients discovered at the dawn of nutrition science in the 19th century.

According to Gyorgy Scrinis, a professor of food politics and policy at the University of Melbourne, there’s an underlying reason that nutrition science fails to fix these persistent, very public problems. In the 1980s, Scrinis had a ‘lightbulb moment’ when he started to question the contemporary trend for engineering food to have less fat. He instead adopted a whole-foods mindset, began to cook more food from scratch, and eventually became an enthusiastic breadmaker – ‘pretty obsessive, actually’ – baking sourdough breads from combinations of whole, often sprouted, grains. In conversation, he recalls nuances about favourite sourdoughs he’s tried during foreign travels, from artisanal French-style bakeries in San Francisco to hole-in-the-wall pizzerias in Rome that use sourdough crusts.

Scrinis argues that the field of nutrition science is under the sway of an ideology he dubbed ‘nutritionism’, a mode of thinking about food that makes a number of erroneous assumptions: it reduces foods to quantified collections of nutrients, pulls foods out of the context of diets and lifestyles, presumes that biomarkers such as body-mass index are accurate indicators of health, overestimates scientists’ understanding of the relationship between nutrients and health, and falls for corporations’ claims that the nutrients they sprinkle into heavily processed junk foods make them healthful. These errors lead us toward food that is processed to optimise its palatability, convenience and nutrient profile, drawing us away from the whole foods that Scrinis says we should be eating. He says the history of margarine provides a tour of the perils of nutritionism: it was first adopted as a cheaper alternative to butter, then promoted as a health food when saturated fat became a nutritional bugbear, later castigated as a nutritional villain riddled with trans fats, and recently reformulated without trans fats, using new processes such as interesterification. That has succeeded in making margarine look better, according to nutritionism’s current trends, but is another kind of ultra-processing that’s likely to diminish the quality of food.

Scrinis says nutritional research is increasingly revealing that modern processing itself makes foods inherently unhealthful. Carlos Monteiro, a nutrition researcher at the University of Sao Paolo in Brazil, says artificial ingredients such as emulsifiers and artificial sweeteners in ‘ultra-processed’ foods throw off how our bodies work. Other researchers say the structure of food changes how the nutrients affect us. For instance, fibre can act differently in the body when it is part of the natural matrix of food than when it’s consumed separately. This kind of research about the limitations of nutritional reductionism is starting to affect public health guidelines. The government of Brazil now integrates this view into its nutritional recommendations, focusing more on the naturalness of foods and de-emphasising an accounting of its nutrients.

While Scrinis cites the growing body of scientific research implicating modern food processing, he also supports his critique of nutritionism with appeals to intuition. ‘This idea that ultra-processed foods are degraded – we’ve always known this,’ he says. ‘Our senses tell us whole foods are wholesome. People know this intuitively. The best foods in terms of cuisine are made from whole foods, not McDonald’s. It’s common sense.’

Even as nutritionism pushes us to believe that the latest nutrition research reveals something important about food, we also hold on to a conflicting concept: the idea that natural foods are better for us in ways that don’t always show up in scientific studies – that whole foods contain an inherent essence that is despoiled by our harsh modern processing techniques. ‘It’s a general attitude that you can break foods down that is the problem,’ says Scrinis. ‘It’s showing no respect for the food itself.’ This idea of respecting food reveals an underlying perspective that is essentialist, which, in philosophy, is the Platonic view that certain eternal and universal characteristics are essential to identity. Science is usually thought of as the antithesis of our atavistic intuitions, yet nutrition science has contained an essentialist view of nutrition for almost a century.

When presented with a range of whole foods, children instinctively chose what was good for them

In 1926, the US paediatrician Clara Davis began what was arguably the world’s most ambitious nutrition experiment. Science had recently shown the importance of vitamins to health, bringing nutrition into the realm of medicine, and doctors who worked in the paternalistic model of the time gave high-handed prescriptions for what children should eat. The journalist Stephen Strauss described this era in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2006:

Armed with growing evidence from the newly emerging field of nutrition, doctors began prescribing with bank teller-like precision what and when and how much a child should eat in order to be healthy … Children quite often responded to doctor-ordered proper diets by shutting down and refusing to eat anything. One physician of the period estimated that 50-90 per cent of visits to paediatricians’ offices involved mothers who were frantic about their children’s refusals to eat – a condition then called anorexia … Alan Brown … head of paediatrics at Toronto’s The Hospital for Sick Children (popularly known as Sick Kids), advised mothers in the 1926 edition of his best-selling book on child-rearing, The Normal Child: Its Care and Feeding, to put children on what was literally a starvation diet until they submitted to eat doctor-sanctioned meals.

Davis rebelled against this tyranny, arguing that children could naturally choose the right foods to keep themselves healthy. She enrolled a group of 15 babies who had never eaten any solid food, either orphans or the children of teenage mothers or widows. She took them to Mount Sinai Hospital in Cleveland and kept them there for between six months and 4.5 years (eventually moving the experiment to Chicago), during which time they never left and had very little outside contact. At every meal, nurses offered the children a selection of simple, unprocessed whole foods, and let them pick what to eat. The children chose very different diets, often making combinations that adults found nasty, and dramatically changed their preferences at unpredictable times. All the children ended up ruddy-cheeked pictures of health, including some who had arrived malnourished or with rickets, a Vitamin D deficiency.

Davis said the study showed that when presented with a range of whole foods, children instinctively chose what was good for them. Dr Spock, the influential childcare expert, promoted the study in his ubiquitous guide, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (1946), saying it showed that parents should offer children ‘a reasonable variety and range of natural and unrefined foods’ and not worry about the specifics of what they choose. This idea, later known as the ‘wisdom of the body’, became an important thread in nutrition, persisting through nutritionism-inspired fads for particular foods and nutrients. When Scrinis lays down criticisms of processed food – such as: ‘Our bodies can detect what a healthful food is. Our bodies are telling us that the most healthful foods are whole foods’ – he is carrying on this essentialist tradition.

Most of us carry both ideologies, essentialism and nutritionism, in our minds, pulling us in different directions, complicating how we make decisions about what to eat. This tension is also visible in nutrition. Many government public health agencies give precise recommendations, based on a century of hard research, for the amounts of every nutrient we need to keep us healthy. They also insist that whole foods, especially fruits and vegetables, are the best ways to get those nutrients. But if you accept the nutrient recommendations, why assume that whole foods are a better way of getting those nutrients than, say, a powdered mix that is objectively superior in terms of cost, convenience and greenhouse emissions? What’s more, powdered mixes make it far easier for people to know exactly what they’re eating, which addresses one problem that constantly vexes nutritionists.

This kind of reflexive preference for natural foods can sometimes blind us to the implications of science. Even as research piles up implicating, for instance, excessive sugar as a particular problem in modern diets, most nutrition authorities refuse to endorse artificial sweeteners as a way to decrease our sugar consumption. ‘I’ve spent a lot of time with artificial sweeteners, and I cannot find any solid evidence there’s anything wrong with including them in your diet,’ says Tamar Haspel, a Washington Post columnist who has been writing about nutrition for more than 20 years. She says there’s some evidence that low-calorie sweeteners help some people lose weight, but you won’t hear that from nutrition authorities, who consistently minimise the positives while focusing on potential downsides that have not been well-established by research, such as worries that they cause cancer or scramble the gut microbiome. Why the determined opposition? ‘Because artificial sweeteners check lots of the boxes of the things that wholesome eaters avoid. It’s a chemical that’s manufactured in a plant. It’s created by the big companies that are selling the rest of the food in our diet, a lot of which is junk.’ Haspel says that nutritionists’ attitude to low-calorie sweeteners is ‘puritanical, it’s holier-than-thou, and it’s breathtakingly condescending’. The puritanical response reflects the purity of essentialism: foods that are not ‘natural’ are not welcome in the diets of right-thinking, healthy-eating people.

Haspel minces no words about the processed foods that stand in perfect formations up and down the long aisles of our supermarkets: they’re engineered to be ‘hyper-palatable’, cheap, convenient and ubiquitous – irresistible and unavoidable. We eat too much, making us increasingly fat and unhealthy. She says the food giants that make processed foods are culpable for these crises, and the people consciously pushing them on children ‘should all be unemployable’.

Our arguments over food are so polarised because they are not only about evidence: they are about values

Yet Haspel says the story of processing doesn’t have to go this way. ‘Here’s what’s getting lost in the shuffle: processing is a tool to do all kinds of things. If you use it to create artificial sweeteners, you’re using processing for good. If you’re using processing to create plant-based beef, I think that’s using processing for good. If you use processing to increase shelf life and reduce food waste, you’re using processing for good,’ she says. But the consensus against low-calorie sweeteners shows a bright, essentialist line: food processing is inherently bad. ‘Unfortunately, the way the processing is playing out, the “good” people say you shouldn’t eat processed foods, and only the “evil” people say you should eat processed food. I think everything in food, like other aspects of our lives, gets polarised. Everything divides people into camps. Processed foods comes along as the issue du jour and you have to be for it or against it.’

Our arguments over food are so polarised because they are not only about evidence: they are about values. Our choice of what we put inside us physically represents what we want inside ourselves spiritually, and that varies so much from person to person. Hearn uses food, much of it from a blender, to hack his body and keep him well-fuelled between business meetings. Scrinis looks forward to spending time in his kitchen, tinkering with new varieties of sourdough packed with sprouted grains and seeds. Haspel lives in Cape Cod, where she grows oysters, raises chickens, and hunts deer for venison – and also drinks diet soda and uses sucralose in her smoothies and oatmeal, to help keep her weight down.

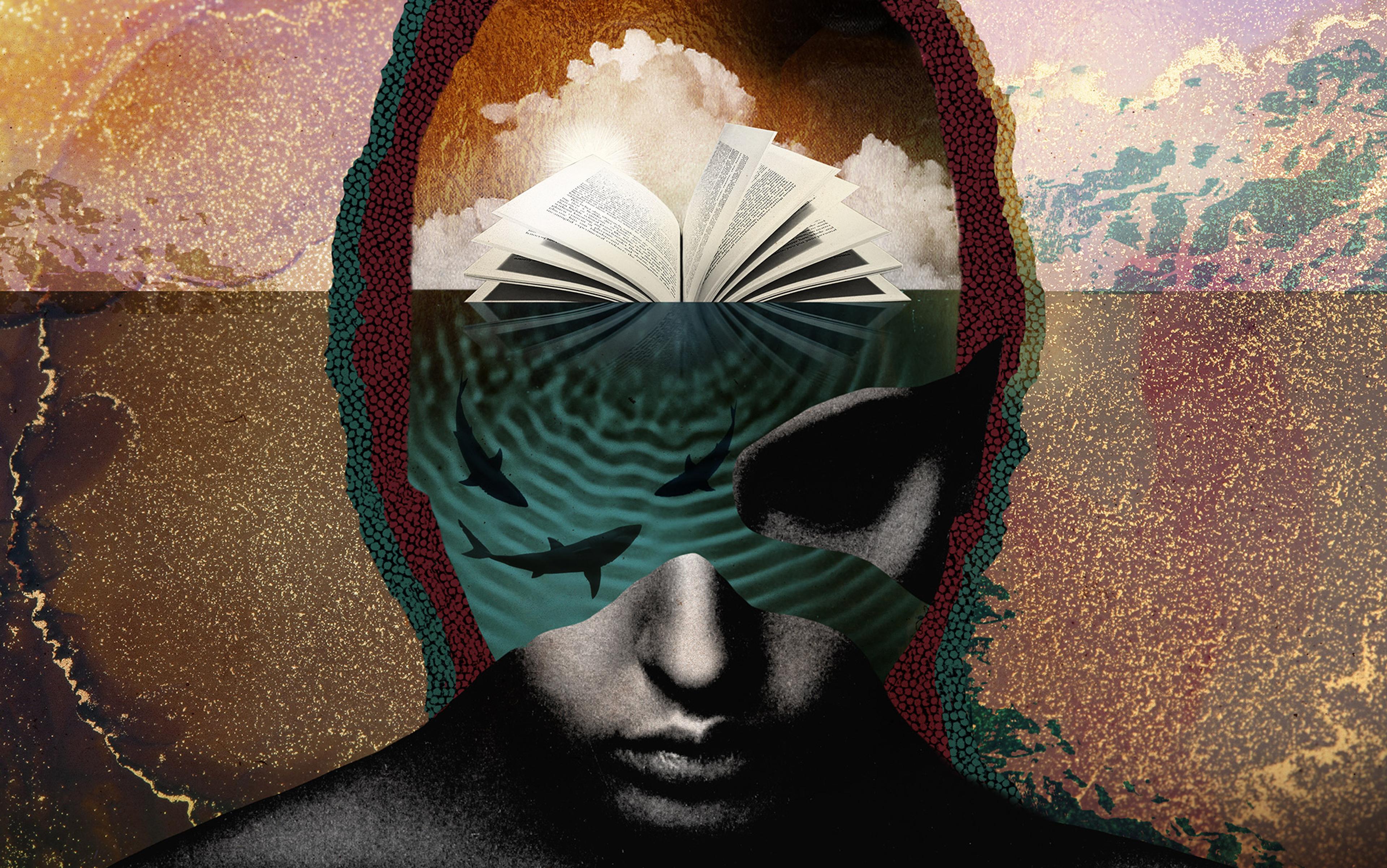

Nutritionism and essentialism provide comfortingly clear perspectives about what makes food healthful. But an open-minded look at the evidence suggests that many of the most hotly debated questions about nutrition are impossible to answer with the information we have, maybe with the information we will ever have in the foreseeable future. If we isolate nutrients and eat them in different forms than they naturally come in, how will they affect us? Can processed foods be made in ways to approach or even surpass the healthfulness of natural whole foods?

Outside of an experiment such as Davis’s unrepeatable study of babies, we can’t know and control exactly what people eat for long periods – and even that project never came close to unravelling diseases that kill old people by the millions. Human bodies are so fascinating in part because they are so variable and malleable. Beyond some important universals, such as the vitamins discovered a century ago, different people’s bodies work differently, because of their genes, behaviours and environments. The food we eat today changes the way our bodies work tomorrow, making yesterday’s guidance out of date. There are too many variables and too few ways to control them.

Scurvy was a nutritional puzzle with relatively few variables. It comes on and can be resolved quickly, it’s reliably caused by – and only by – the shortage of one chemical, and it’s pretty consistent across individuals. Yet even in the era of modern science, more than a century after the British navy mandated a preventative that had been shown to work, some of the leading scientists of the day still managed to talk themselves from the right explanation to wrong ones. If scurvy was so resistant to correct explanation, we can imagine how much harder it will be to fully understand how food relates to far more complicated scourges such as cancer, heart disease and dementia.

But there’s a flip side to that frustration. Maybe the reason that diet is so difficult to optimise is that there is no optimal diet. We are enormously flexible omnivores who can live healthily on varied diets, like our hunter-gatherer ancestors or modern people filling shopping carts at globally sourced supermarkets, yet we can also live on specialised diets, like traditional Inuits who mostly ate a small range of Arctic animals or subsistence farmers who ate little besides a few grains they grew. Aaron Carroll, a physician in Indiana and a columnist at The New York Times, argues that people spend far too much time worrying about eating the wrong things. ‘The “dangers” from these things are so very small that, if they bring you enough happiness, that likely outweighs the downsides,’ he said in 2018. ‘So much of our food discussions are moralising and fear-inducing. Food isn’t poison, and this is pretty much the healthiest people have even been in the history of mankind. Food isn’t killing us.’

Food is a vehicle for ideologies such as nutritionism and essentialism, for deeply held desires such as connecting with nature and engineering a better future. We argue so passionately about food because we are not just looking for health – we’re looking for meaning. Maybe, if meals help provide a sense of meaning for your life, that is the healthiest thing you can hope for.